Keywords: Mesenchymal stem cells, Exosomes, Cell death, Ferroptosis, Neurodegenerative diseases, Cancer, Regenerative medicine, Oxidative stress

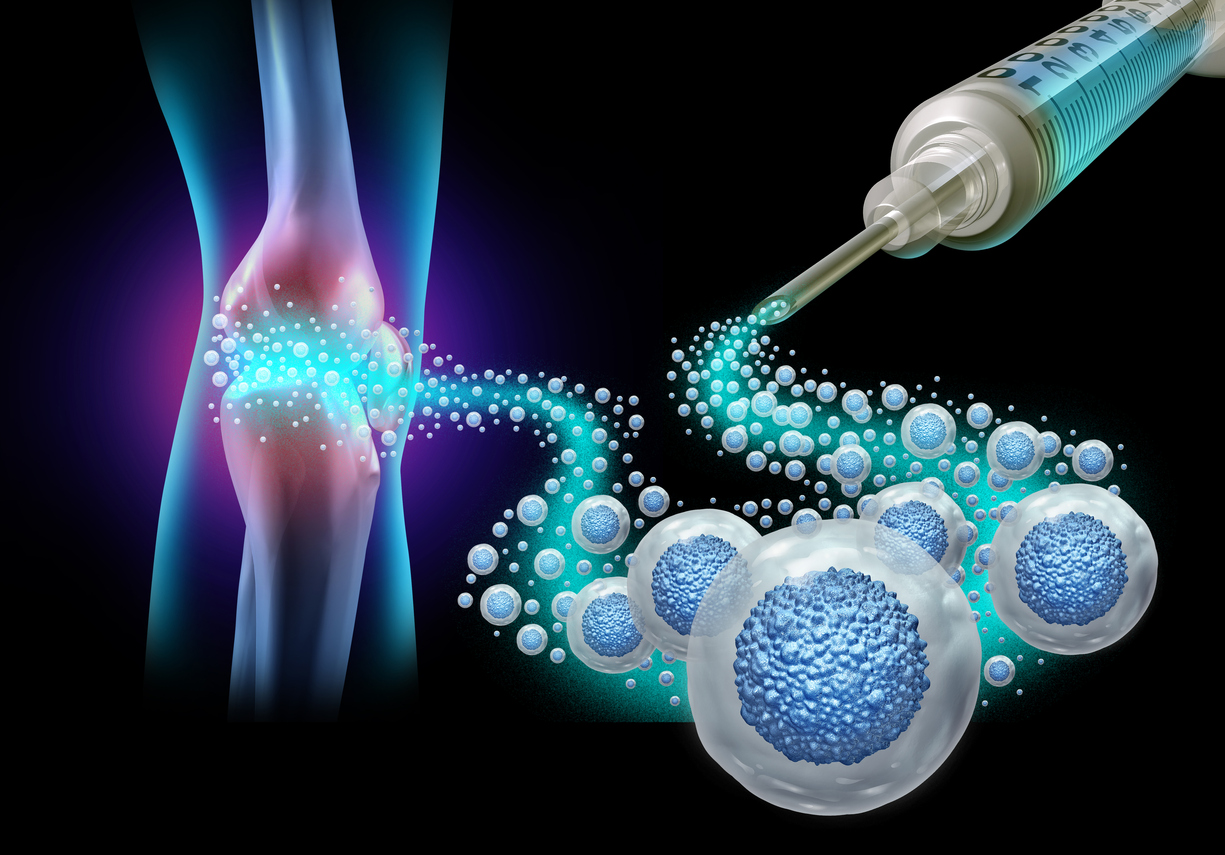

Graphical Abstract

graphic file with name 13287_2025_4511_Figa_HTML.jpg

Background

Ferroptosis, a regulated type of cell death resulting from iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, has been recognized as a crucial mechanism associated with the development of various diseases, including neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, digestive, musculoskeletal, and cancer-related diseases [1]. Although pharmacological compounds aimed at inducing ferroptosis, such as erastin and RSL3, or inhibiting it, such as ferrostatin-1 (fer-1), have demonstrated potential in preclinical studies, their application in clinical settings faces challenges, including off-target effects and limited tissue specificity [2–6]. This has sparked interest in innovative therapeutic approaches, especially those utilizing mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos), which are known for their natural biocompatibility and diverse cytoprotective effects [7].

MSC-Exos, which are nano-sized extracellular vesicles (30–150 nm) loaded with bioactive materials such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, have demonstrated significant therapeutic potential in tissue repair and immunomodulation [7–9]. Unlike whole-cell therapies, MSC-Exos mitigate risks associated with tumor formation and immune rejection while maintaining the regenerative and anti-inflammatory properties of their parent cells [10]. Recent research emphasizes the capability of MSC-Exos to deliver antioxidant enzymes, microRNAs, and iron-regulating molecules [11], positioning them as promising candidates for targeting ferroptosis. The therapeutic potential of MSC-Exos in disorders caused by ferroptosis is further underscored by their effectiveness in reducing oxidative stress, decreasing lipid peroxidation, and inhibiting ferroptotic cell death [12, 13]. In conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, ferroptosis has been linked to neuronal injury due to iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation in the brain [14]. A key benefit of MSC-Exos is their capability to cross biological barriers, including the blood-brain barrier (BBB), allowing for targeted delivery to otherwise difficult-to-reach tissues [15, 16]. This characteristic is particularly significant for treating central nervous system disorders, where systemic drug administration is often ineffective.

Emerging evidence also implicates Exos in modulating the tumor microenvironment to reduce ferroptosis resistance in cancer [17]. Certain tumors escape ferroptosis by upregulating system xc⁻ (a cystine/glutamate antiporter composed of SLC7A11 and SLC3A2) or glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), a key enzyme that reduces lipid hydroperoxides and protects cells from ferroptotic death [1]. These protective mechanisms can be disrupted by exosomal miRNAs that stop these pathways [18]. Conversely, MSC-Exos may protect non-malignant tissues from chemotherapy-induced ferroptosis, as seen in cisplatin-treated HK-2 cells [19]. This dual role of exposing cancer cells while protecting healthy tissues makes MSC-Exos multipurpose tools in oncology. In conclusion, MSC-Exos present an innovative therapeutic approach for disorders related to ferroptosis, combining natural compatibility with tailored precision. With continued research, MSC-Exos have the potential to revolutionize treatment strategies for conditions associated with iron dysregulation and oxidative stress. This article summarizes current progress in understanding the machinery of Exos biogenesis. In addition, we provide a comprehensive review of recent advancements in utilizing MSC-Exos as a therapeutic strategy to modulate ferroptosis in different disease models. We critically evaluate the emerging evidence demonstrating that MSC Exos are enriched with anti-ferroptotic miRNAs, antioxidant enzymes, and iron homeostasis regulators, which can mitigate cellular ferroptosis.

Characteristics of MSCs

MSCs have acquired considerable interest in regenerative medicine due to their multipotent and self-renewing properties, along with their active release of a wide array of trophic factors [20–24]. These cells can be isolated from a wide range of tissues, such as bone marrow, adipose tissue, dental pulp, umbilical cord, blood, placenta, hair, synovial fluid, liver, and heart [25–30]. MSCs are also characterized by unique surface markers that distinguish them from other cell types, including CD44, CD73, CD90, and CD105, while lacking expression of CD45, CD34, CD14, CD11b, CD79α, CD19, and HLA-DR surface molecules [31–35]. Classified as multipotent stem cells, MSCs can differentiate into various cellular phenotypes, including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes [25, 32, 36, 37]. MSCs have been shown to exhibit anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties, primarily mediated through direct interactions with immune cells [38–40]. Studies have revealed that MSCs secrete several soluble factors that contribute to their immunomodulatory effects and regulate immune cell responses [41, 42].

It was initially hypothesized that following in vivo injection, MSCs contribute to tissue regeneration by migrating to the site of injury, engrafting, and differentiating into the appropriate cell type to replace damaged cells. However, this traditional view has been challenged by evidence from numerous clinical studies [43, 44]. In reality, MSCs do not directly substitute for injured tissues. Instead, their therapeutic benefits are mainly brought about by the release of paracrine factors [28, 45, 46]. In addition to these soluble factors, MSCs also release Exos, which are extracellular vesicles (EVs) that carry functional molecules such as messenger RNAs (mRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), peptides, proteins, cytokines, and lipids to recipient cells [47–49]. Exos are a subtype of EVs, which are cell-derived structures enclosed by lipid bilayer membranes [50]. EVs play a critical role in intercellular communication by transporting bioactive proteins, lipids, and RNAs, making them a valuable source of circulating biomarkers for various diseases [49, 51–53]. Based on their biogenesis and size, EVs are classified into three main subtypes: Exos (30–150 nm in diameter), microvesicles (150–1000 nm in diameter), and apoptotic bodies (50–2000 nm in diameter) (recently reviewed [54–56]. These nano-sized vesicles are essential mediators of intercellular communication and play a pivotal role in tissue repair and regeneration, underscoring the therapeutic potential of MSCs in regenerative medicine [57].

In contrast to MSCs, MSC-Exos represent an acellular therapeutic approach that holds significant potential to overcome the limitations associated with cell-based therapies. These limitations include cytotoxicity, immune rejection, regulatory obstacles, senescence and inflammation, and limited targeting precision [10, 58, 59]. Furthermore, MSC-Exos serve as promising carriers for a wide range of pharmacological agents and demonstrate superior transfection efficiency for nucleic acid delivery compared to MSCs themselves [60, 61]. Unlike MSCs, which undergo senescence after a limited number of passages or with aging [59, 62], MSC-Exos do not exhibit signs of senescence and are more cost-effective and easier to produce at scale for clinical applications [63, 64].

Biogenesis of Exos

Unlike microvesicles, which are formed through direct outward budding from the plasma membrane, Exos are specifically created within multivesicular bodies (MVBs) through the endolysosomal pathway [50, 65]. They are discharged into the extracellular space upon the fusion of MVBs with the plasma membrane [65] (Fig. 1). This mechanism underscores their definite origin in contrast to other types of EVs. While the endosome-dependent pathway is acknowledged as a principal mechanism for Exos biogenesis, certain investigations indicate that direct budding from the plasma membrane also contributes to a considerable fraction of Exos formation [47, 66, 67]. The endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) machinery, including ESCRT-I and ESCRT-II complexes, initiate the budding process at the endosomal membrane, leading to the formation of intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within MVBs (Fig. 1). ESCRT-III, in conjunction with associated proteins, facilitates the final split of vesicles and participates in protein deubiquitination. These ILVs are subsequently released as Exos when the MVBs fuse with the plasma membrane [47, 50, 66] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1

Open in a new tab

Schematic representation of the biogenesis of exosomes released from mesenchymal stem cells (MSC-Exos). (A) The biogenesis of Exos begins with the creation of early Exos through the invagination of the plasma membrane, followed by the development of late Exos through the selection of specific cargo. It ultimately leads to the formation of multivesicular bodies (MVBs). MVBs contain intraluminal vesicles (ILVs). (B) The molecular components of endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, -III) and their interaction to form and release ILVs have been illustrated. Created with BioRender.com

Composition and classification of Exos

Exos are membrane-enclosed nanovesicles with a diameter of 30–150 nm that carry a diverse array of bioactive molecules reflective of their cell of origin (Fig. 2). Their unique composition enables them to facilitate intercellular communication by transmitting signals among disparate cells, thereby modulating numerous biological processes [50, 57] (Fig. 2). Extensive research has identified a wide range of exosomal components, including over 41,860 proteins, 7,540 RNAs, and 1,116 lipids, underscoring the complexity and heterogeneity of exosomal cargo [50]. EVpedia, a comprehensive database, catalogs 92,897 proteins, 27,642 mRNAs, 4,934 miRNAs, and 584 lipids derived from 538 studies across 33 different species, further highlighting the diversity of exosomal constituents [68].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2

Open in a new tab

The composition and therapeutic roles of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos). (A) MSC-Exos contain cytokines, proteins, lipids, mRNAs, miRNAs, and ncRNAs. MSC-Exos possesses several therapeutic benefits, such as immunomodulatory effects, promotion of cell survival, differentiation and migration, anti-apoptotic activities, and the ability to enhance angiogenesis. (B) The uptake of Exos by the recipient cell through direct interaction with specific receptors on the plasma membrane, plasma membrane fusion, and by endocytosis. After uptake, Exos deliver exosomal cargo to specific organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (1); Exos cargo release by fusion with the endosomal membrane (2); undergo lysosomal degradation (3); fuse with a lysosome and releasing the soluble cargo of Exos (4); be trafficked back to the plasma membrane for re-secretion (5). Created with BioRender.com

Nucleic acids

Exos contain various nucleic acids, including mRNAs, miRNAs, and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). These molecules play critical roles in regulating cellular processes, including cell proliferation, migration, angiogenesis, and epigenetic modification [69] (Fig. 2).

Protein components

This category includes both cytoplasmic and membrane-associated proteins, such as receptors, enzymes, transcription factors, ECM proteins, and MHC proteins [70] (Fig. 2). They can be further categorized as.

General components: These are widely distributed proteins found in Exos regardless of their origin. They play a crucial role in the processes of vesicle biogenesis and exocytosis, including membrane transport proteins (such as Rab GTPases), heat shock proteins (such as HSP70 and HSP90), and ESCRT-related proteins (such as Tsg101 and Alix) [71] (Fig. 2).

Specific components: These proteins are unique to the parent cells from which the Exos are derived and are closely associated with their cellular origin. For example, CD45 and MHC-II are markers derived from antigen-presenting cells [53, 72, 73].

The predominant proteins are constituents of the tetraspanin family, a classification of scaffolding membrane proteins that contains CD63, CD81, and CD9. These proteins are packed into Exos during biogenesis and are situated at the exosomal surface and function as unique markers [47, 63, 74] (Fig. 2).

Lipids

Exos are enriched with a variety of lipids, such as hexosylceramides, sphingomyelin, cholesterol, and phospholipids. These lipids are essential for maintaining exosomal structural integrity and functionality, particularly in their role as drug-delivery vehicles [75]. In addition, Exos can encapsulate cytokines and transcription factor receptors, further enhancing their role in intercellular communication and material exchange [65] (Fig. 2).

Exos can be categorized based on whether they are modified artificially, distinguishing between natural and engineered Exos. Natural Exos can be further divided into eukaryotic and prokaryotic Exos. Prokaryotic Exos primarily come from bacterial sources. Eukaryotic Exos include those produced by animals and plants. Exos originating from animals can be divided into normal Exos, which are secreted by healthy cells, and tumor Exos, which come from tumor cells [76]. Normal Exos are released by nearly all cell types and are abundantly found in various bodily fluids, including saliva, blood plasma, urine, ascites, milk, and bile [77]. MSCs are an example of a normal cell type that releases Exos, which have shown specific therapeutic advantages for different diseases [78], such as myocardial ischemia [79, 80], neurological disorders [81], and skeletal diseases [82]. Generally, Exos from different sources exhibit variations in their yield, composition, functionality, and drug-loading capacity [83], which can result in diverse therapeutic outcomes. Interestingly, Exos have also been implicated not only in tissue healing and repair but also in the progression of various diseases [84].

Overview of ferroptosis: mechanisms and therapeutic potential

Ferroptosis is characterized by the accumulation of lipid peroxides, distinguishing it from apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy [85]. This process is driven by the failure of cellular antioxidant defenses, particularly the GPX4 system, which neutralizes typically lipid peroxides using glutathione (GSH) [86, 87]. Central to ferroptosis is the dysregulation of iron metabolism, which is typically controlled by iron-regulatory proteins, such as transferrin and ferritin. Excess intracellular iron catalyzes Fenton reactions, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) that oxidize polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in membranes [88], resulting in membrane rupture and cell death (Fig. 3). Morphologically, ferroptosis involves mitochondrial shrinkage and increased membrane density, reflecting its unique metabolic imbalances [89, 90]. Another important process underlying ferroptosis depends on the interplay between lipid peroxidation and antioxidant defense mechanisms [2]. The system xc⁻ facilitates the uptake of cystine to produce GSH, which is essential for GPX4 activity (Fig. 3). Blocking system xc⁻ or GPX4 results in reduced GSH levels, which delays the removal of lipid peroxides. Another significant component is the acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) enzyme, which contributes to the peroxidation of PUFAs [86, 91] (Fig. 3). Genetic factors such as p53 and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) also affect susceptibility by regulating the expression of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) or influencing antioxidant defenses [92].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3

Open in a new tab

The ferroptosis pathways. The primary metabolic processes involved in ferroptosis can be classified into three main categories: iron metabolism, the GSH/GPX4 pathway, and lipid peroxidation. Ferrous ions (Fe2+) contribute to the accumulation of lipid peroxides via the Fenton reaction and the oxidation of lipids. Cystine is reduced to cysteine, which is utilized to synthesize glutathione (GSH). GPX4 can reduce harmful lipid peroxides. Long-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 (ACSL4) facilitates the attachment of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) to phospholipids, resulting in the formation of polyunsaturated fatty acid-containing phospholipids (PUFA-PLs), which can subsequently be oxidized to lipid peroxides. Different cargo molecules of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes can target different ferroptosis-related signaling pathways. Created with BioRender.com

The therapeutic manipulation of ferroptosis has gained interest in diseases where iron and oxidative stress contribute to pathological mechanisms [93, 94]. In cancer, inducers of ferroptosis, such as erastin and RSL3, take advantage of the high levels of iron and PUFAs in tumor cells [94, 95], while inhibitors like fer-1 and liproxstatin-1 show potential in treating neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s, where lipid peroxidation contributes to neuronal damage [96]. Ischemia-reperfusion injury in the heart and kidney also involves ferroptotic pathways, underscoring the importance of specific modulation based on the context. While there are obstacles in reaching targeted tissue delivery and reducing off-target effects, strategies involving nanoparticles and small-molecule inhibitors are actively being investigated [97, 98]. Despite the preclinical promise shown by pharmacological agents that target ferroptosis-such as inducers like erastin and RSL3, and inhibitors like fer-1-their application in clinical settings encounters difficulties, which include unintended effects and restricted tissue specificity [2, 99]. These challenges have led to increased interest in innovative therapeutic approaches, such as MSC-Exos, which are naturally biocompatible and possess diverse cytoprotective characteristics (Fig. 3).

Crosstalk between MSC-Exos and ferroptosis

Exos exhibit context-dependent regulatory roles, influenced by their cellular origin and microenvironment. In pathological conditions, endogenous Exos can worsen disease progression by inducing ferroptosis in target cells [100]. For instance, exosomal miR-140-5p suppresses SLC7A11 expression, impairing the system xc-/GSH/GPX4 axis, reducing GSH synthesis, and promoting cardiomyocyte ferroptosis and cardiac injury [101]. Conversely, exogenous MSC-Exos have emerged as promising therapeutic tools to suppress ferroptosis in diverse diseases, as will be discussed in the later sections.

Ferroptosis regulation via the NAD(P)H/FSP1/CoQ10 pathway is another Exos-mediated mechanism [17]. Exosomal RNAs, such as miR-4443, modulate FSP1 expression, a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor, altering cellular resistance to lipid peroxidation and contributing to disease outcomes [102] (Fig. 3). Notably, miR-4443 has been implicated in tumorigenesis, metastasis, and chemotherapy resistance, underscoring its dual role in cancer progression [103]. An additional mechanistic investigation revealed that LncGm36569, which is significantly expressed in MSC-Exos, can bind to its competing endogenous RNA, miR-5627-5p, leading to an increase in the expression of its target gene FSP1 [104]. This action consequently inhibits ferroptosis and facilitates the restoration of nerve function [104]. Iron homeostasis is critical for cellular survival, and dysregulation of iron metabolism proteins by endogenous Exos can drive ferroptosis [100]. For example, bone marrow-derived MSCs (BMSCs) transplantation faces challenges due to microenvironmental stressors that induce ferroptosis. Engineering BMSCs to overexpress HO-1 enhances Exos yield and functionality, prolonging their retention and therapeutic efficacy in vivo [105]. In oncology, Exos can control tumor progression by modulating lipid metabolism, a process complexly linked to ferroptosis [100]. Human urine-derived stem cell-Exos (HuSC-Exos) enriched with the long non-coding RNA TUG1 mitigates ferroptosis and cellular damage [106]. This protective effect involves TUG1 binding to the RNA splicing factor 1, which stabilizes ACSL4 mRNA- a key driver of lipid peroxidation- highlighting a novel axis for therapeutic intervention.

MSC-Exos targets ferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases

Neurodegenerative disorders represent a category of incurable diseases manifesting as a slow deterioration in cognitive function, which notably impacts the quality of life for patients [107]. This progression is driven by motor and cognitive impairments, including memory decline [108]. As neurons depend on iron to meet high energy requirements and are abundant in PUFAs [109, 110], they are susceptible to ferroptosis. Growing evidence indicates that ferroptosis is a crucial factor in the development of neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Parkinson’s disease (PD) [14, 111]. One of the primary obstacles in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases is the limited transport of large molecules into the brain due to the BBB. This barrier severely restricts drug delivery and prevents potentially effective central nervous system treatments from being used clinically [112]. This issue underscores the necessity for alternative drug delivery methods, leading to the emergence of Exos as a promising therapeutic option for neurodegenerative diseases [113]. Their nanoscale size allows them to cross the BBB and serve as natural carriers of bioactive molecules secreted by their parent cells or engineered drug delivery systems. These characteristics, as previously discussed, make Exos a viable strategy to overcome the limitations of traditional central nervous system therapies. This is why MSC-Exos can serve as a promising strategy to target ferroptosis while also overcoming the challenges posed by the BBB (Table 1).

Table 1.

Role of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) against ferroptosis in different diseases

System Disease Model Source of exosomes Molecular mediators Target/pathway Outcomes Ref.

Nervous System Alzheimer’s disease Wistar rat BMSCs IL-6/IL-10 /VEGF ROS Block ROS and synapse damage induced by Aβ in hippocampal neurons [119]

C57/BL6 transgenic mice HucMSCs IDE/NEP Aβ Decrease proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α, and clear Aβ deposition [120]

Parkinson’s disease C57BL/6 mice NSCs CDC42 ACSL4 Inhibit ACSL4-related ferroptosis and alleviate vascular injury [133]

Stroke C57BL/6 mice BMSCs Irisin YAP/EGR1/ACSL4 Inhibit YAP/EGR1/ACSL4-mediated ferroptosis [137]

C57/BL6

mice

ADSCs

Fxr2

M2pep-ADSC-Exo

Atf3/ SLC7A11

M2 microglia

Inhibit ferroptosis of M2 microglia, suppress the inflammation, and promote neuronal survival [138]

Sprague-Dawley rats UCMSCs circBBS2 miR-494/SLC7A11 Reduce ferroptosis and relieve ischemic stroke [139]

C57BL/6 mice BMSCs Fer-1 GPX4/COX2 Inhibit neural ferroptosis and ameliorate cerebral I/R injury [140]

C57BL/6 mice ADSCs IRP2 miR-19b-3p Decrease neurological damage and intracerebral haemorrhage [141]

C57BL/6 mice BMSCs LPO and MDA SRC3 Reduce ferroptosis of the neurons and inhibite the activation of microglia and astrocytes [142]

C57BL/6 mice BMSCs – HSPA5/GPX4 Decrease the modified neurological severity score and brain water content [143]

Delayed neurocognitive recovery C57BL/6 mice BMSCs SIRT1/ Nrf2/ HO-1 ROS Inhibit ferroptosis and mitigate neurocognitive decline [144]

Acute spinal cord injury

C57BL/6

mice

BMSCs FTH-1/ SLC7A11/ FSP1/ GPX4 Nrf2/GCH1/BH4 Inhibit ferroptosis and enhance neurological recovery in SCI models [146]

Cardiovascular System Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury

C57BL/6

mice

BMSCs Mir9-3hg Pum2/ PRDX6 Inhibit cardiomyocytes’ ferroptosis and improve cardiac dysfunction [149]

BALB/c

mice

BMSCs miR-330-3p BAP1/SLC7A11/IP3R Inhibit cardiomyocytes from ferroptosis [151]

DOX-induced cardiotoxicity

C57BL/6

mice

UCMSCs Trx1 mTORC1 Inhibit DOX-induced ferroptosis, decrease iron content, MDA, increase GSH and GPX4, and enhance cardioprotection [150]

Myocardial injury

C57BL/6J

mice

UCMSCs miR-23a-3p DMT1 Inhibit ferroptosis and attenuate myocardial injury [152]

Digestive System Inflammatory bowel diseases

BABL/c

mice

UCMSCs miR-129-5p ACSL4 Inhibit ferroptosis and lipid peroxidation, restore intestinal antioxidant balance and reduce inflammation [157]

BALB/c mice ERCs – ACSL4/GSH/GPX4 Alleviate ulcerative colitis through regulation of ferroptosis, iron, GSH, MDA, GPX4, and ACSL4 [158]

Acute liver injury BALB/c-nu/nu mice UCMSCs GPX1 ROS Promote the recovery of hepatic oxidant injury through the delivery of GPX1 [164]

C57BL/6

mice

BMSCs CD44/ OTUB1 SLC7A11/ system xC− Protect against ferroptosis by maintaining SLC7A11 function via CD44/OTUB1 [166]

C57BL/6

mice

MSCs P62 Keap1-Nrf2 Inhibit ROS production and lipid peroxide-induced ferroptosis [167]

SD rats HO1/BMMSCs miR-124-3p Lipid/ROS/Fe2+ Inhibit hepatocyte ferroptosis by downregulating the level of Steap3, and reducing the IRI of the grafts [168]

Immune System Osteoarthritis

C57BL/6

mice

MSCs – GOT1/CCR2/Nrf2/HO-1 Reduce inflammation levels and prevent ferroptosis [174]

Sprague-Dawley rat BMSCs – METTL3-m6A-/ACSL4 Reduce chondrocyte ferroptosis and prevent OA [175]

Cancer Colorectal cancer ob/ob mice ADSCs MTTP xCT/ZEB1/GPX4 Inhibit ferroptosis by decreasing the polyunsaturated fatty acids ratio and lipid ROS levels, and increasing the sensitivity to chemotherapy [182]

Hepatocellular carcinoma BALB/c ADSCs miR-122 CCNG1/ ADAM10/ IGF1R Increase chemosensitivity and enhance Sorafenib’s antitumor effects. [178]

HCC patients HucMSCs miR-451a ADAM10 Reduce HCC proliferation and metastasis [186]

Wound Diabetic wound

BALB/c

mice

BMSCs circ-Snhg11 SLC7A11/GPX4 Enhance anti-ferroptosis signals and improve angiogenesis [193]

DB/DB

mice

HucMSCs coenzyme Q10 ACSL4 Inhibit ferroptosis and promote cell proliferation and migration [194]

BALB/c mice BMSCs Circ-ITCH Nrf2 Alleviate high glucose-induced ferroptosis and improve the angiogenesis ability [195]

C57BL/6 mice hucMSCs miR-17–92 – Accelerate cell proliferation, migration, angiogenesis, and enhance resistance against erastin-induced ferroptosis [196]

Other Diseases Acute lung injury C57BL/6 mice ADSCs – SIRT1/Nrf2/HO-1 Reduce lung tissue injury, oxidative stress, and ferroptosis [210]

BALB/c

mice

ADSCs miR-125b-5p Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 Alleviate oxidative stress injury and ferroptosis of lung tissue [211]

SD rats HucMSCs – Nrf2/HO-1 Inhibit ferroptosis and alleviate lung inflammation [213]

Radiation-induced lung injury C57BL/6 mice HucMSCs miR-486-5p SMAD2/Akt Suppress ferroptosis and fibrosis in lung epithelial cells [212]

Chronic kidney disease C57BL/6 mice DPSCs – Keap1-Nrf2/GPX4 Inhibit ferroptosis, reduce inflammation and oxidative stress [218]

Acute kidney injury C57BL/6 mice USCs lncRNA TUG1 SRSF1/ACSL4 Improve kidney function and ameliorate ferroptosis [106]

Open in a new tab

Alzheimer’s disease

AD is a progressive neurodegenerative condition identified by the presence of amyloid-β plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles in the central nervous system [114]. Growing evidence indicates ferroptosis in AD pathogenesis, with studies reporting iron accumulation, dysregulated antioxidant systems, elevated lipid peroxidation, and impaired anti-ferroptotic defenses in AD brains [115]. A recent study by Sun et al. [116] identified five ferroptosis-related genes (DDIT4, MUC1, KLHL24, CD44, and RB1) as key contributors to AD progression. Aβ was found to be associated with ferroptosis pathways in post-mortem human brain tissue affected by AD [117]. Notably, oxidative stress-a well-established inducer of ferroptosis-has also been recognized as a critical driver of AD pathology [118]. This mechanistic overlap highlights a need for potential therapeutic targeting of ferroptosis. For instance, de Godoy et al. demonstrated that BMSC-Exos reduces ROS in Aβ-exposed hippocampal neurons in vitro and mitigates oxidative damage [119]. In addition, Ding et al. reported that HucMSC-Exos could reduce neuroinflammation by modulating microglial activation, enhancing Aβ clearance, and restoring cognitive function in AD mouse models [120]. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing a significantly reduced neuronal Aβ accumulation, enhanced neurogenesis, and promoted cognitive recovery by MSC-Exos [121–123].

Parkinson’s disease

PD is characterized by a gradual loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and the accumulation of intracellular aggregates of misfolded α-synuclein that causes motor dysfunction [124]. Pathological hallmarks of PD are closely associated with ferroptotic mechanisms, including iron accumulation, increased lipid peroxidation, and deficiencies in antioxidant defenses [125–127]. α-Synuclein, a key pathological hallmark of PD, interacts with iron and activates ferroptosis-related pathways [128, 129]. Increased levels of soluble α-synuclein are associated with higher levels of lipid peroxidation, a characteristic frequently noticed in patients with PD [130]. Furthermore, α-synuclein may exacerbate oxidative stress by promoting cytosolic dopamine accumulation [131]. Genetic studies reinforce this connection: mutations in ferroptosis-associated genes, such as DJ-1 (a negative regulator of ferroptosis linked to autosomal recessive PD) and ACSL4, have been implicated in PD susceptibility [132]. Despite persistent mechanistic links between ferroptosis and PD, translational research exploring Exos-based therapies to target ferroptosis remains in its early stages. A recent preclinical study demonstrated that CDC42, a protein derived from hypoxia-pretreated neural stem cell Exos, mitigates vascular damage in PD mice by modulating the ACSL4-dependent ferroptosis pathway [133]. Interestingly, the knockdown of CDC42 inhibited cell viability and angiogenesis and augmented ferroptosis and lipid-ROS levels, which were restored by fer-1 and liproxstatin-1.

Stroke

Cerebral stroke, which includes ischemic and hemorrhagic types, remains one of the leading causes of death and prolonged disability globally, frequently leading to permanent brain injury [134]. Increasing research indicates that ferroptosis plays a key role in causing secondary damage in both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. Approaches aimed at addressing ferroptosis have demonstrated the potential to reduce brain injury after a stroke, highlighting its importance in the underlying pathology [135, 136]. For instance, BMSC-Exos enriched with irisin-a peptide derived from FNDC5-overexpressing cells-enhanced neuronal viability, suppressed ferroptosis, and improved functional recovery in ischemic stroke models [137]. They found that BMSC-FNDC5-Exos inhibited the YAP/EGR1/ACSL4 axis, a key ferroptosis regulator. Similarly, Wang et al. reported that Exos derived from adipose-derived stem cells (ADSC-Exos) deliver Fxr2, which stabilizes Atf3 mRNA in M2 microglia, therapy inhibiting ferroptosis, reducing inflammation and promoting neuronal survival [138]. In their results, engineering ADSC-Exos with M2pep-a peptide ligand targeting M2 microglia- enhanced their cellular specificity and further amplified their anti-ferroptotic effects both in vitro and in vivo.

Further advances include Exos derived from umbilical cord MSCs (UCMSC-Exos), which alleviate ischemic injury by delivering circBBS2. This circular RNA, downregulated in stroke patients, acts as a sponge for miR-494, upregulating the ferroptosis inhibitor SLC7A11. This mechanism reduced lipid peroxidation, improved neuronal survival, and attenuated ischemic damage in preclinical models [139]. In addition, MSC-Exos loaded with fer-1 was shown to mitigate cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by delivering fer-1 to neurons, thereby reducing apoptosis, inflammation, and ferroptotic cell death while enhancing viability [140]. Furthermore, Yi et al. showed that the overexpression of miR-19b-3p from ADSC-Exos can directly target iron regulatory protein, resulting in decreased neurological damage and intracerebral haemorrhage caused by ferroptosis [141]. BMSC-Exos overexpressing GFP or SRC-3 have been used to treat mouse models of cerebral ischemia. The findings indicated that SRC3-Exo treatment significantly reduced neuronal ferroptosis and inhibited the activation of microglia and astrocytes. In addition, the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain was decreased, and neurological performance was improved in the treated animals [142]. Similarly, IL-1β-induced BMSC-Exos reversed hemin-induced ferroptosis in neuronal cells, including high iron, ROS, malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), and reduced GSH level and cell viability [143]. The same study demonstrated that BMSC-Exos could suppress neuronal ferroptosis in an animal model of intracerebral hemorrhage through the HSPA5/GPX4 pathway. Exos administration also decreased the modified neurological severity score and brain water content and improved pathological damage in mice.

Delayed neurocognitive recovery

Delayed neurocognitive recovery (NCR), a common postoperative neurological complication in the aged, is characterized by acute cognitive dysfunction and memory deficits. Recent in vivo studies demonstrate that MSC-Exos mitigate cognitive decline in aged mice with dNCR [144]. The results showed by Liu et al. revealed that BMSC-Exos suppress hippocampal ferroptosis and upregulate key antioxidant proteins, including SIRT1, Nrf2, and HO-1, which enhance cellular resistance to oxidative damage.

Acute spinal cord injury (ASCI)

ASCI is a severe and prevalent neurological condition that significantly impacts society in terms of physical and socioeconomic aspects [145]. Recent studies have demonstrated that BMSC-Exos can promote neurological recovery in ASCI by inhibiting ferroptosis through the Nrf2/GTP cyclohydrolase I (GCH1)/5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) signaling axis, reducing oxidative stress, and enhancing the expression of ferroptosis suppressors [146].

MSC-Exos target ferroptosis in cardiovascular diseases

Cardiovascular diseases involve a broad range of disorders, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, acute myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, cardiomyopathy, valvular heart diseases, congenital heart defects, and heart failure [147]. A significant link between ferroptosis and the development of various cardiovascular conditions has been reviewed [148]. Furthermore, increasing attention has been directed toward using MSC-Exos to inhibit ferroptosis in cardiovascular diseases (Table 1). A recent investigation revealed that BMSC-Exos can protect against ischemia-reperfusion injury by preventing cardiomyocyte ferroptosis [149]. They found that lncRNA miR9-3hg present in BMSC-Exos downregulates pumilio homolog 2, reducing peroxiredoxin 6 expression, leading to diminished oxidative stress and ferroptosis. Another study compared the impacts of normoxic and hypoxic human UCMSC-Exos in mitigating doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through ferroptosis inhibition [150]. Hypo-Exos demonstrated superior protective effects by lowering oxidative stress and iron accumulation and enhancing GPX4 levels. The underlying mechanism involved thioredoxin 1-induced activation of mTORC1, which facilitated GPX4 synthesis and decreased ferroptosis.

Furthermore, Xiao et al. examined the influence of GATA-4 overexpressing BMSC-Exos (BMSCs-ExosGATA−4) on the protection of cardiomyocytes from hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced ferroptosis [151]. BMSC-ExosGATA−4 inhibited ferroptosis through the upregulation of miR-330-3p, which negatively regulates BAP1, thereby preventing the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction. Song et al. also explored the cardioprotective function of human UCMSC-Exos in the prevention of ferroptosis-induced myocardial damage [152]. UCMSC-Exos mitigated ferroptosis and decreased myocardial injury; however, these beneficial effects were contradicted by the knockout of miR-23a-3p. This study suggests that UCMSC-Exos inhibit DMT1 with assistance from miR-23a-3p to protect the heart from ferroptosis. Similarly, Man et al. found that Exos released from pericardial adipose tissue interacted with iron regulatory protein 2, helping to protect cardiomyocytes from ferroptosis while maintaining iron homeostasis disrupted by Adipsin [153].

MSC-Exos target ferroptosis in the digestive system

Disorders of the digestive system comprise a broad range of medical conditions that pose risks to the overall health of populations [154]. Among these disorders are inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), which are characterized by ulcerative colitis and demonstrated to be associated with ferroptosis [155, 156]. Recent evidence shows that UCMSC-Exos alleviate IBDs by delivering miR-129-5p, which targets ACSL4 to inhibit ferroptosis and lipid peroxidation, restoring intestinal antioxidant balance and reducing inflammation [157]. In another study, endometrial regenerative cell-derived-Exos also alleviated ulcerative colitis and inhibited ferroptosis [158]. This treatment reduced iron levels, lipid peroxidation, and ACSL4 expression while increasing GSH and GPX4, ultimately reducing inflammation and improving colon health.

Acute liver injury (ALI) is a severe metabolic disorder caused by hepatocyte damage, often linked to oxidative stress and iron dysregulation [159, 160]. Ferroptosis has emerged as a key contributor to ALI pathogenesis [160]. Recent studies implicate ferroptosis inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for ALI, targeting iron overload and lipid peroxidation. For instance, Wu et al. demonstrated that fibroblast growth factor 21 mitigates iron overload-induced liver damage and fibrosis by suppressing ferroptosis [161]. Similarly, Niu et al. reported that preventing voltage-dependent anion channel 1 oligomerization preserves mitochondrial integrity and reduces ferroptosis in ALI [162]. MSC-Exos have also shown therapeutic potential, alleviating oxidative stress and apoptosis in murine ALI models [163, 164]. These Exos improve outcomes in drug-induced liver injury and fibrosis [60, 165]. In the context of ferroptosis, Lin et al. revealed that MSC-Exos inhibits ferroptosis in ALI mice by restoring SLC7A11 and GSH production [166]. They found that SLC7A11 downregulation in ALI exacerbates carbon tetrachloride-induced ferroptosis, while MSC-Exos enhance SLC7A11 expression via CD44 and OTUB1 upregulation, supporting antioxidant defenses. In a related study, Zhao et al. demonstrated that baicalin-pretreated MSC-Exos (Ba-Exos) attenuate D-galactosamine/lipopolysaccharide-induced ALI by suppressing ROS and lipid peroxidation [167]. The results highlight the dual role of Ba-Exos in mitigating oxidative stress and ferroptosis, suggesting a novel therapeutic avenue. The above studies have underscored ferroptosis as a pivotal mechanism in ALI and positioned MSC-Exos as a multifaceted intervention, targeting SLC7A11, lipid peroxidation, and mitochondrial integrity. Further research is needed to optimize Exos-based therapies and translate these insights into clinical applications.

Recent research has shown that ferroptosis significantly contributes to ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) in the liver and kidney [160]. Wu et al. found that Exos from hemeified bone marrow MSCs (HO-1/BMSCs) effectively reduced hepatocyte ferroptosis by delivering miR-124-3p, which led to a significant decrease in the iron homeostasis factor, prostate six transmembrane epithelial antigen 3 [168]. Li et al. showed that Exos from HO-1/BMSCs containing miR-29a-3p mitigated hepatic IRI by negatively regulating IREB2 protein levels, lowering intracellular Fe2+ concentrations, increasing lipid ROS levels, and inhibiting ferroptosis [169] (Table 1).

MSC-Exos target ferroptosis in osteoarthritis (OA)

OA is one of the most common types of musculoskeletal disorders globally [170]. It has been proposed that ferroptosis may be involved in the development of OA [171–173]. MSC-Exos have demonstrated their therapeutic ability to improve OA by reducing inflammation, preventing ferroptosis, and promoting bone cell growth through the GOT1/CCR2/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway [174]. Furthermore, BMSC-Exos protect against OA by reducing chondrocyte ferroptosis via the METTL3-m6A-ACSL4 axis. BMSC-Exos limit oxidative stress, inhibit cell death and ACSL4 expression, and prevent OA progression [175] (Table 1).

MSC-Exos regulate cancer ferroptosis

Cancer is a widespread and fatal disease globally; however, current treatment methods, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapies, and immunotherapy, demonstrate limited success in effectively treating cancer [176]. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate alternative methods to trigger cancer-specific cell death and address resistance to anti-tumor medications. Several studies have explored the association between ferroptosis and cancer development and suppression [95] (Table 1). MSC-Exos play a significant role in facilitating chemoresistance in tumor cells; thus, understanding the mechanisms behind this resistance can significantly improve treatment efficacy and patient outcomes [177]. New findings regarding the role of MSC-Exos in mediating resistance to cancer therapies have emphasized their potential to enhance treatment efficacy. Due to their ability to communicate intercellularly, they have low immunogenicity, minimal toxicity, biodegradable nature, and the ability to cross biological barriers, MSC-Exos have become promising vehicles for various biomolecules and chemical agents in cancer treatment. Bioengineered MSC-Exos can encapsulate targeted therapeutic agents, including miRNAs, proteins, and drugs. Research has shown that MSCs modified with synthetic miRNAs can improve the sensitivity of cancer cells to chemotherapy by transferring specific miRNAs through Exos [178–180].

Cancers affecting the digestive system, such as those of the esophagus, stomach, liver, pancreas, and intestines, are among the top causes of cancer-related mortality, with limited available treatments [181]. The effect of MSC-Exos in moderating ferroptosis and impacting treatment resistance has been illustrated in a recent investigation of colorectal cancer [182]. In this study, the authors demonstrated that ADSC-Exos contributes to chemoresistance in colorectal cancer by inhibiting ferroptosis. Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTTP), an abundant protein in ADSC-Exos, mitigates lipid ROS accumulation through the PRAP1/ZEB1/GPX4 signaling pathway. Inhibiting MTTP restores ferroptosis and enhances sensitivity to oxaliplatin, indicating a promising therapeutic target. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) resists common chemotherapy drugs like 5-FU and doxorubicin. Thus, new therapeutic strategies are required. ADSCs transfected with miR-122 successfully transfer miR-122 via Exos to HCC cells, increasing chemosensitivity and enhancing sorafenib’s effects in vivo [178]. The study found that the exosomal SP94-Lamp2bRRM, which targets HCC, aids in delivering small interfering RNA to improve sorafenib-induced ferroptosis by inhibiting the expression of GPX4 and DHODH. This process eventually enhances HCC’s responsiveness to sorafenib [183]. Similarly, BMSC-Exos carrying siGRP78 target GRP78, suppress HCC proliferation, and restore sorafenib efficacy [184]. It has been shown that miR-98, linked to tumor progression, is downregulated in HCC. Overexpressing miR-98 reduces tumor growth and metastasis by inhibiting SALL4, known to inhibit ferroptosis [185]. Also, UCMSCs-derived exosomal miR-451a may inhibit epithelial-mesenchymal transition in HCC by targeting ADAM10, contributing to ferroptosis [186].

Despite significant improvements in radiotherapy techniques, cancer patients frequently experience radiation-related damage either during or after treatment. MSC-Exos have demonstrated the ability to aid in the regeneration of tissue injuries in various diseases and clinical scenarios, such as wound healing, cardiovascular diseases, and COVID-19 [187].

MSC-Exos target ferroptosis in diabetic wounds

Wound healing involves four phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and tissue remodeling [188]. These phases and their physiological functions must occur in the proper sequence and for a specified duration and intensity. Emerging research has found that ferroptosis is involved in these phases and different forms of wound healing. For instance, Li et al. found that, in diabetic ulcers, the levels of ROS, MDA, and lipid peroxidation in fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells subjected to high glucose settings are significantly increased [189]. Furthermore, high glucose decreases the cell survival rate and migration activity. The authors also reported that ferroptosis is significantly triggered in diabetic wounds in both in vitro and in vivo, as confirmed by decreased GPX4 and SLC7A11 expressions and elevated transferrin receptor gene expression levels. In the same study, fer-1 accelerated wound healing in diabetic rats by inhibiting ferroptosis by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Irradiated wounds are common skin lesions encountered in medical practice, primarily resulting from radiotherapy for cancer-related radiation incidents [190]. It has been demonstrated that high levels of UVB exposure can trigger inflammation and induce cell death in human keratinocytes through ferroptosis, which can be inhibited by the compound fer-1 [191]. This excessive exposure to UV rays leads to a depletion of GSH, thus disturbing the redox balance. The studies mentioned above highlight the connection between compromised wound healing and ferroptosis.

Recent advances in regenerative medicine have highlighted the therapeutic potential of MSC-Exos to manage impaired wound healing in diabetic conditions. Three studies elucidate new mechanisms and strategies to target ferroptosis to promote tissue repair (Table 1). Lu et al. identified dysfunctional mitochondria in neutrophils play a crucial role in forming neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), worsening wound healing in diabetes by triggering ferroptosis in endothelial cells [192]. Their findings indicate that NETs inhibit the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, which hinders angiogenesis. To break this cycle, the researchers administered MSC-EVs enriched with functional mitochondria. This approach significantly improved angiogenesis and accelerated wound repair in diabetic models, underscoring the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in NET-mediated pathology. Another study demonstrated that BMSC-Exos promote healing in diabetic wounds via the circular RNA circ-Snhg11 [193]. Silencing circ-Snhg11 reduced the therapeutic benefits of Exos, while its overexpression facilitated angiogenesis and inhibited GPX4-driven ferroptosis. Lastly, Yang et al. examined the effects of MSC-Exos primed with coenzyme Q10 (Q10-Exos) to mitigate ferroptosis in diabetic keratinocytes [194]. Under high glucose conditions, Q10-Exos delivered miR-548ai and miR-660 to human keratinocytes, directly suppressing ACSL4 expression. This miRNA-mediated inhibition restored HaCaT proliferation and migration, while in vivo studies demonstrated accelerated wound closure in diabetic mice. These studies underscore MSC-Exos as versatile vehicles for delivering functional mitochondria, non-coding RNAs, or enzyme-activated components to counteract ferroptosis in diabetic wounds. By targeting different molecular pathways-mitochondrial dysfunction, miR-144-3p/SLC7A11, and ACSL4-these approaches aim to improve angiogenesis and cell survival, presenting promising options for clinical application. Chen and his colleagues demonstrated that BMSCs-Exos through exosomal circ-ITCH could alleviate ferroptosis in the diabetes mellitus model and improve the angiogenesis ability of HUVECs [195]. Similarly, hucMSCs-exosomal miR–17–92 promotes wound healing by inducing angiogenesis and inhibiting ferroptosis [196].

MSC-Exos target ferroptosis in other diseases

Ferroptosis mechanisms play an important role in the pathogenesis of lung and kidney diseases. Numerous studies have shown that impaired lung function is a key predictor of both morbidity and mortality, potentially promoting the progression of different disease processes [197, 198]. A range of factors play a role in the emergence of lung disorders, with one recent focus being ferroptosis. Recent research has revealed a strong association between ferroptosis and the onset of several lung disorders, including acute lung injury [199–201], lung ischemia-reperfusion injury [202, 203], pulmonary fibrosis [204], asthma [205], pulmonary tuberculosis [206, 207], and recently, COVID-19 [208, 209]. The prospect of addressing various lung diseases by targeting ferroptosis using MSC-Exos has gained interest (Table 1). A recent study indicated that ADSC-Exos protect against acute lung injury induced by sepsis by preventing macrophage M1 polarization, reducing inflammation, and inhibiting ferroptosis via the SIRT1/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway [210]. ADSC-Exos were also demonstrated to protect pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells from inflammation-induced ferroptosis in sepsis-related acute lung injury by delivering miR-125b-5p, which inhibits Keap1 and activates Nrf2/GPX4 signaling. In a further sepsis model, ADSC-Exos decreased oxidative stress, ferroptosis, and lung tissue damage, ultimately improving survival rates [211]. A recent study engineered MSC-Exos modified with both SARS-CoV-2-S-RBD and miR-486-5p to improve lung targeting and therapeutic effectiveness against radiation-induced lung injury [212]. These engineered MSC-Exos inhibited ferroptosis and fibrosis in lung epithelial cells by inhibiting SMAD2, a key protein in TGF-β signaling, and Akt, a protein involved in cell survival and growth. This ultimately improved survival rates and reduced long-term fibrosis in angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 humanized mice. Finally, UCMSC-Exos were demonstrated to protect against burn-induced acute lung injury by inhibiting ferroptosis by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway [213]. UCMSC-Exos mainly reduced inflammation, restored antioxidant defenses, and prevented iron overload, offering potential treatment for burn-induced lung damage.

Kidney disorders, ranging from acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease, significantly impact quality of life [214]. Renal disease is usually characterized by oxidative stress, various types of cell death, a complex microenvironment with inflammation, and a reduction in renal units [215]. Ferroptosis has been linked to the pathogenesis and development of kidney diseases [215–217]. In this context, MSC-Exos have been investigated to target ferroptosis in renal diseases. For instance, a recent study showed that dental pulp stem cell (DPSC)-Exos may help in treating chronic kidney disease by inhibiting ferroptosis through the Keap1-Nrf2/GPX4 pathway [218]. Furthermore, Sun et al., showed that HuSC-Exos protect against kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury by reducing ferroptosis via lncRNA taurine upregulated gene 1, which regulates ACSL4 through serine arginine-rich splicing factor 1 interaction, suggesting a potential acute kidney injury therapy [72, 106] (Table 1).

Comparative analysis of MSC-Exos and alternative therapeutic approaches for targeting ferroptosis

MSC-Exos vs. Exos from other cell populations

Regarding the mechanistic advantages of MSC-Exos in suppressing ferroptosis, MSC-Exos display unique anti-ferroptotic properties when compared to Exos derived from other cell types. MSC-Exos prevent ferroptosis through various mechanisms, including the delivery and regulation of GPX4, as shown in different experimental models [150, 158]. Moreover, MSC-Exos contain miRNAs that stimulate the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway [211], maintain the stability and function of SLC7A11 [166], and mitigate iron overload via DMT1 modulation [152]. In contrast, Exos derived from cancer cells, such as HCC and colorectal cancer play an essential role in affecting the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment by mediating ferroptosis in immune cells [219, 220]. Exos derived from specific immune cells can exacerbate ferroptosis. For example, macrophage-derived Exos induce endothelial ferroptosis and barrier disruption during cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury via thrombospondin-1-mediated binding to OTUD5 and promotion of GPX4 ubiquitination [221]. In terms of therapeutic potential and clinical relevance, MSC-Exos are ideal for therapeutic use due to their consistent anti-ferroptotic and regenerative properties. Animals model investigations reveal that they reduce ferroptosis in various disease models by restoring redox balance [222]. In contrast, Exos derived from cancer cells are being investigated for their potential selectively to induce ferroptosis in tumors. In the myocardial injury model, cardiac fibroblast-derived Exos inhibit SLC7A11 expression and stimulate cardiac ferroptosis by delivering miR-23a-3p [223]. The biocompatibility and low immunogenicity of MSC-Exos make them safer for systemic applications [224].

MSC-Exos vs. small-molecule inhibitors

Current therapeutic approaches comprise small-molecule inhibitors such as Fer-1, iron chelators, and genetic modifications [225, 226]. MSC-Exos, however, persistently modulate the cellular microenvironment, promoting tissue repair alongside ferroptosis suppression [104]. For example, in ALI, MSC-Exos downregulated liver Ptgs2 and LOXs mRNA levels and reduced lipid peroxidation [166]. This suggests that MSC-Exos may have a comparable therapeutic effect in protecting against ferroptosis-induced liver injury. In contrast, Fer-1 is a radical-trapping antioxidant but lacks regenerative or iron-regulatory capabilities [227]. However, these small molecules show rapid efficacy in acute models, but their effects are transient and require repeated dosing. Fer-1 faces bioavailability and metabolic stability obstacles, with a notably short plasma half-life and imperfect penetration through the BBB, limiting its use in neurodegenerative conditions [99, 228, 229]. Iron chelators (e.g., deferoxamine) reduce iron overload but disturb physiological iron homeostasis [230]. While biocompatible, MSC-Exos also face challenges (which are discussed in the limitations and future perspectives section). Future investigations should focus on optimizing Exos engineering for targeted delivery and standardizing production processes. Combining MSC-Exos with radical-trapping antioxidants or iron chelators could produce synergistic therapies, harnessing rapid radical scavenging alongside prolonged microenvironment modulation.

Clinical application of MSC-Exos in ferroptosis

The preclinical studies discussed throughout our review have shown promising results and hold great potential for future clinical applications. MSC-Exos are considered promising therapeutic agents for ferroptosis due to their robust regulatory effects on ferroptotic pathways [231]. Iron chelators and antioxidant agents have been evaluated in clinical trials. For instance, a 24-month single-blind study using Desferrioxamine revealed a reduction in the progression rate of AD compared to the control group [232]. Deferiprone is another chelating agent used in a randomized controlled trial that demonstrated improvements in neurological scores and symptoms related to iron dysregulation [233]. Various antioxidants, including vitamin E, α-lipoic acid, and selenium, have been used in clinical trials for AD treatment, many of which can inhibit lipid peroxidation and thus prevent ferroptosis. In a clinical study of AD patients, alpha-lipoic acid slowed cognitive decline [234]. Recent studies have identified specific Exos-mediated pathways critical for ferroptosis, offering a novel strategy for its clinical applications [17, 231]. Although Exos have entered clinical trials and shown beneficial effects in various diseases [235], trials specifically investigating MSC-Exos for ferroptosis remain limited in the literature and registered clinical trials. The lack of clinical trials may be attributed to the relatively recent identification of ferroptosis and the ongoing investigations of its mechanistic links to Exos. Several challenges continue to hinder the clinical application of Exos in ferroptosis-related conditions. Defining the appropriate dosage of MSC-Exos for therapeutic efficacy remains a key challenge, as standardized dosing regimens are yet to be established. Future studies should focus on determining dose-response relationships and optimizing administration frequency and volume. Moreover, the scalability of exosome production is critical for clinical translation, necessitating the development of robust bioprocessing and purification platforms.

Collaborative proposals aimed at overcoming these challenges could unlock the clinical possibilities of Exos, establishing them as a fundamental component of next-generation therapies for ferroptosis. By applying insights from current trials in other areas, researchers may accelerate the development of MSC-Exos-based approaches for treating ferroptosis.

Limitations and future perspectives

Ferroptosis has been recognized as a vital cell death mechanism in different disorders such as neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, digestive, musculoskeletal, skin, pulmonary, renal diseases, and cancer. MSC-Exos show great potential in modulating ferroptosis but still face significant challenges. These challenges include variations in Exos composition due to differences in stem cell origin, cultivation methods, and isolation techniques [236]. Modification strategies such as optimizing cell culture conditions, genetically modifying source cells, or refining Exos isolation techniques can increase the yield of EVs [237, 238]. Furthermore, achieving efficient delivery of Exos to affected tissues remains a major challenge. Modification techniques such as surface modification with targeting ligands or engineering vesicles to carry specific receptors can improve their targeting capability [239]. Robust manufacturing processes to ensure the consistency and scalability of EV production are still lacking. Therefore, multiple bioreactor configurations operating in dynamic culture conditions have been developed [240]. Prolonged Exos administration might inhibit immune surveillance and trigger autoimmune responses, increasing susceptibility to infections or malignancies. Thus, amendment methods such as membrane engineering or removal of immunogenic components can mitigate immune reactions and improve the vesicles’ immunomodulatory properties [241]. Modification approaches such as electroporation, sonication, or exogenous loading methods can enhance cargo loading efficiency, ensuring effective delivery of therapeutic molecules [242]. In addition to the abovementioned limitation, the lack of clinical data beyond preclinical trials limits their potential application in clinical settings.

The limitation regarding the application of Exos in ferroptosis-targeted strategies lies in the incomplete understanding of how Exos regulate ferroptosis. Although Exos are known to influence iron regulation as well as the expression of GPX4 and SLC7A11, the particular regulatory pathways require additional investigation. Furthermore, whether Exos regulate other molecules implicated in GSH synthesis or iron metabolism to affect ferroptosis remains an open question.

The natural capacity of Exos to carry bioactive molecules such as lipids, proteins, and RNAs, combined with their role in managing oxidative stress and inflammation, makes them excellent nanocarriers. Enhancing Exos for delivering specific drugs or genetic materials and their innate immunomodulatory and tissue-repair properties can improve therapeutic precision. Advances such as CRISPR and surface modifications allow for the customization of Exos for tailored therapies, aligning with the goals of precision medicine [243, 244]. In addition, the combination of Exos with antioxidants, iron chelators, or other therapeutic agents could boost their efficacy. These developments position MSC-Exos as a revolutionary approach to tackling challenges related to ferroptosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that they have not use AI-generated work in this manuscript.

Abbreviations

4-HNE

4-Hydroxynonenal

ACSL4

Acyl coenzyme A synthetase long-chain family member 4

AD

Alzheimer’s disease

ADSCs

Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells

ALI

Acute liver injury

ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

BBB

Blood-brain barrier

BMSCs

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

DMT1

Divalent metal transporter 1

dNCR

Delayed neurocognitive recovery

DPSCs

Dental pulp stem cells

ECM

Extracellular matrix

ESCRT

Endosomal sorting complexes required for transport

EVs

Extracellular vesicles

Exos

Exosomes

Fer-1

Ferrostatin-1

FSP1

Ferroptosis suppressor protein 1

GPx

Glutathione peroxidase

GPX4

Glutathione peroxidase 4

GSH

Glutathione

HO-1

Heme oxygenase-1

HucMSCs

Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells

ILVs

Intraluminal vesicles

IRI

Ischaemia-Reperfusion injury

MDA

Malondialdehyde

miRNAs

microRNAs

MSCs

Mesenchymal stem cells

MTTP

Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein

MVBs

Multivesicular bodies

NCOA4

Nuclear receptor coactivator 4

ncRNAs

Non-coding RNAs

NETs

Neutrophil extracellular traps

Nrf2

Nuclear factor-erythroid 2 related factor 2

OA

Osteoarthritis

PD

Parkinson’s disease

PUFA

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

ROS

Reactive oxygen species

SLC7A11

Solute carrier family 7 member 11

SRSF1

Serine arginine-rich splicing factor 1

STEAP3

Six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3

HuSCs

Human urine-derived stem cells

Author contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z., E.E. and BH-J.; Investigation, M.Z, E.E., P.E., and BH-J.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, M.Z, E.E., and P.E.; Writing-review and editing, M.Z., and BH-J.; Supervision, M.Z. and BH-J.; Funding acquisition, BH-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2025-00517133). This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the NRF of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (2017R1A6A1A03015876). This research was supported by a Korea Basic Science Institute (National Research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant funded by the Ministry of Education (grant No. 2021R1A6C101C369).

Data availability

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Mohammed Zayed and Enas Elwakeel contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Mohammed Zayed, Email: mzayed2@vet.svu.edu.eg.

Byung-Hoon Jeong, Email: bhjeong@jbnu.ac.kr.

References

1.Dixon SJKM, Lemberg MR, Lamprecht, et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060–72. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2.Stockwell BRJP, Friedmann Angeli H, Bayir, et al. Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death Nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 2017;171(2):273–85. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3.Yan JL, Bao H, Liang, et al. A druglike Ferrostatin-1 analogue as a ferroptosis inhibitor and photoluminescent Indicator. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2025. 10.1002/anie.202502195. e202502195.DOI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4.Zhang JF, Lin Y, Xiao, et al. Discovery and optimization of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives as novel ferroptosis inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2025;284:117192. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2024.117192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5.Alves FD, Lane TPM, Nguyen AI, Bush S, Ayton. In defence of ferroptosis. Signal Transduct Target Therapy. 2025;10(1). 10.1038/s41392-024-02088-5. p. 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

6.Zhang LYL, Luo Y, Xiang XY, Bai RR, Qiang X, Zhang YL, Yang XL, Liu. Ferroptosis inhibitors: past, present and future. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15–2024. 10.3389/fphar.2024.1407335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

7.Hade MDCN, Suire Z, Suo. Mesenchymal stem Cell-Derived exosomes: applications in regenerative medicine. Cells. 2021;10(8). 10.3390/cells10081959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

8.Rani SAE, Ryan MD, Griffin T, Ritter. Mesenchymal stem Cell-derived extracellular vesicles: toward Cell-free therapeutic applications. Mol Ther. 2015;23(5):812–23. 10.1038/mt.2015.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9.Tan FX, Li Z, Wang J, Li K, Shahzad J, Zheng. Clinical applications of stem cell-derived exosomes. Signal Transduct Target Therapy. 2024;9(1):17. 10.1038/s41392-023-01704-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10.Phinney DGMF, Pittenger C, Review. MSC-Derived exosomes for Cell-Free therapy. Stem Cells. 2017;35(4):851–8. 10.1002/stem.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11.Zhang LW, Bai Y, Peng Y, Lin M, Tian. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes provide neuroprotection in traumatic brain injury through the LncRNA TUBB6/Nrf2 pathway. Brain Res. 2024;1824:148689. 10.1016/j.brainres.2023.148689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12.Yang RZWN, Xu HL, Zheng XF, Zheng B, Li LS, Jiang SD, Jiang. Exosomes derived from vascular endothelial cells antagonize glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis by inhibiting ferritinophagy with resultant limited ferroptosis of osteoblasts. J Cell Physiol. 2021;236(9):6691–705. 10.1002/jcp.30331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13.Ito FK, Kato I, Yanatori T, Murohara S, Toyokuni. Ferroptosis-dependent extracellular vesicles from macrophage contribute to asbestos-induced mesothelial carcinogenesis through loading ferritin. Redox Biol. 2021;47:102174. 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14.Fei YY, Ding. The role of ferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Cell Neurosci. 2024;18:1475934. 10.3389/fncel.2024.1475934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15.Elliott ROM, He. Unlocking the power of exosomes for crossing biological barriers in drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(1). 10.3390/pharmaceutics13010122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

16.Jeppesen DKAM, Fenix JL, Franklin, et al. Reassessment Exosome Composition Cell. 2019;177(2):428–45. e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17.Wu JZ, Li Y, Wu N, Cui. The crosstalk between exosomes and ferroptosis: a review. Cell Death Discovery. 2024;10(1):170. 10.1038/s41420-024-01938-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18.Xu QL, Zhou G, Yang F, Meng Y, Wan L, Wang L, Zhang. CircIL4R facilitates the tumorigenesis and inhibits ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating the miR-541-3p/GPX4 axis. Cell Biol Int. 2020;44(11):2344–56. 10.1002/cbin.11444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19.Yu YM, Chen Q, Guo, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell exosome-derived miR-874-3p targeting RIPK1/PGAM5 attenuates kidney tubular epithelial cell damage. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2023;28(1):12. 10.1186/s11658-023-00425-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20.Pittenger MFDE, Discher BM, Péault DG, Phinney JM, Hare AI, Caplan. Mesenchymal stem cell perspective: cell biology to clinical progress. Npj Regenerative Med. 2019;4(1):22. 10.1038/s41536-019-0083-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21.Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 1991;9(5):641–50. 10.1002/jor.1100090504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22.Zayed MSH, Kook BH, Jeong. Potential therapeutic use of stem cells for prion diseases. Cells. 2023;12(19). 10.3390/cells12192413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

23.Mahmoud E, Mohamed MA, Noby AA, Abdel-Hady M, Zayed. Treatment strategies for meniscal lesions: from past to prospective therapeutics. Regen Med. 2022;17(8):547–60. 10.2217/rme-2021-0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24.Zayed MY-C, Kim B-H, Jeong. Therapeutic effects of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells combined with glymphatic system activation in prion disease. Mol Neurodegeneration. 2025;20(1):42. 10.1186/s13024-025-00835-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25.Zayed MC, Caniglia N, Misk MS, Dhar. Donor-Matched comparison of chondrogenic potential of equine bone Marrow- and synovial Fluid-Derived mesenchymal stem cells: implications for cartilage tissue regeneration. Front Vet Sci. 2016;3:121. 10.3389/fvets.2016.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26.Hass RC, Kasper S, Böhm R, Jacobs. Different populations and sources of human mesenchymal stem cells (MSC): A comparison of adult and neonatal tissue-derived MSC. Cell Commun Signal. 2011;9:12. 10.1186/1478-811x-9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27.Costela-Ruiz VJL, Melguizo-Rodríguez C, Bellotti R, Illescas-Montes D, Stanco CR, Arciola E, Lucarelli. Different sources of mesenchymal stem cells for tissue regeneration: A guide to identifying the most favorable one in orthopedics and dentistry applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(11). 10.3390/ijms23116356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

28.Zayed MK, Iohara H, Watanabe M, Ishikawa M, Tominaga M, Nakashima. Characterization of stable hypoxia-preconditioned dental pulp stem cells compared with mobilized dental pulp stem cells for application for pulp regenerative therapy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):302. 10.1186/s13287-021-02240-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29.Zayed MNJ, Schumacher N, Misk MS, Dhar. Effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines on chondrogenesis of equine mesenchymal stromal cells derived from bone marrow or synovial fluid. Vet J. 2016;217:26–32. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30.Zayed MS, Adair M, Dhar. Effects of normal synovial fluid and interferon gamma on chondrogenic capability and Immunomodulatory potential respectively on equine mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(12). 10.3390/ijms22126391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

31.Ramos L, Sánchez-Abarca TLI, Muntión S, et al. MSC surface markers (CD44, CD73, and CD90) can identify human MSC-derived extracellular vesicles by conventional flow cytometry. Cell Communication Signal. 2016;14:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32.Barry FPJM, Murphy. Mesenchymal stem cells: clinical applications and biological characterization. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(4):568–84. 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33.Camilleri ETMP, Gustafson A, Dudakovic, et al. Identification and validation of multiple cell surface markers of clinical-grade adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells as novel release criteria for good manufacturing practice-compliant production. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7(1):107. 10.1186/s13287-016-0370-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34.Dominici MK, Le Blanc I, Mueller, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The international society for cellular therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315–7. 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35.Zayed MBH, Jeong. Adipose-Derived mesenchymal stem cell secretome attenuates prion protein peptide (106–126)-Induced oxidative stress via Nrf2 activation. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2025;21(2):589–92. 10.1007/s12015-024-10811-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36.Lee RHB, Kim I, Choi H, Kim HS, Choi K, Suh YC, Bae JS, Jung. Characterization and expression analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from human bone marrow and adipose tissue. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2004;14(4–6):311–24. 10.1159/000080341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37.Zayed MYC, Kim BH, Jeong. Biological characteristics and transcriptomic profile of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells isolated from prion-infected murine model. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;16(1):154. 10.1186/s13287-025-04273-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38.Wu XJ, Jiang Z, Gu J, Zhang Y, Chen X, Liu. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapies: Immunomodulatory properties and clinical progress. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):345. 10.1186/s13287-020-01855-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39.Li PQ, Ou S, Shi C, Shao. Immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cells/dental stem cells and their therapeutic applications. Cell Mol Immunol. 2023;20(6):558–69. 10.1038/s41423-023-00998-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40.Zayed MK, Iohara. Immunomodulation and regeneration properties of dental pulp stem cells: A potential therapy to treat coronavirus disease 2019. Cell Transpl. 2020;29:963689720952089. 10.1177/0963689720952089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41.Song NM, Scholtemeijer K, Shah. Mesenchymal stem cell immunomodulation: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2020;41(9):653–64. 10.1016/j.tips.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42.Gao FSM, Chiu DAL, Motan Z, Zhang L, Chen HL, Ji HF, Tse QL, Fu Q, Lian. Mesenchymal stem cells and immunomodulation: current status and future prospects. Cell Death & Disease, 2016. 7(1): pp. e2062-e2062.10.1038/cddis.2015.327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

43.Caplan AID, Correa. The MSC: an injury drugstore. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9(1):11–5. 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44.Gnecchi MZ, Zhang A, Ni VJ, Dzau. Paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell signaling and therapy. Circ Res. 2008;103(11):1204–19. 10.1161/circresaha.108.176826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45.Prockop DJ. Concise review: two negative feedback loops place mesenchymal stem/stromal cells at the center of early regulators of inflammation. Stem Cells. 2013;31(10):2042–6. 10.1002/stem.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46.Lee RH, A.A. Pulin MJ, Seo DJ, Kota J, Ylostalo BL, Larson L, Semprun-Prieto P, Delafontaine DJ, Prockop. Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5(1):54–63. 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47.Joo HS, Suh JH, Lee HJ, Bang ES, Lee JM. Current knowledge and future perspectives on mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes as a new therapeutic agent. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(3):727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48.Nikfarjam SJ, Rezaie NM, Zolbanin R, Jafari. Mesenchymal stem cell derived-exosomes: a modern approach in translational medicine. J Translational Med. 2020;18:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49.Kalluri RVS, LeBleu. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367(6478). 10.1126/science.aau6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

50.Colombo MG, Raposo C, Théry. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:255–89. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51.Janockova JL, Slovinska D, Harvanova T, Spakova J, Rosocha. New therapeutic approaches of mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes. J Biomed Sci. 2021;28:1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52.van Niel GG, D’Angelo G, Raposo. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(4):213–28. 10.1038/nrm.2017.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53.Yáñez-Mó MPR, Siljander Z, Andreu, et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:27066. 10.3402/jev.v4.27066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54.Kumar MASK, Baba HQ, Sadida, et al. Extracellular vesicles as tools and targets in therapy for diseases. Signal Transduct Target Therapy. 2024;9(1):27. 10.1038/s41392-024-01735-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55.Tang PF, Song Y, Chen, et al. Preparation and characterization of extracellular vesicles and their cutting-edge applications in regenerative medicine. Appl Mater Today. 2024;37:102084. 10.1016/j.apmt.2024.102084. [Google Scholar]

56.Takakura YR, Hanayama K, Akiyoshi, et al. Quality and safety considerations for therapeutic products based on extracellular vesicles. Pharm Res. 2024;41(8):1573–94. 10.1007/s11095-024-03757-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57.Marote AFG, Teixeira B, Mendes-Pinheiro AJ, Salgado. MSCs-derived exosomes: cell-secreted nanovesicles with regenerative potential. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58.Zayed MK, Iohara. Effects of p-Cresol on senescence, survival, inflammation, and odontoblast differentiation in canine dental pulp stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(18). 10.3390/ijms21186931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

59.Zayed MK, Iohara AR. Senescence, apoptosis, and inflammation profiles in periodontal ligament cells from canine teeth. Curr Mol Med. 2023;23(8):808–14. 10.2174/1566524022666220520124630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60.Lou GZ, Chen M, Zheng Y, Liu. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes as a new therapeutic strategy for liver diseases. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49(6):e346. 10.1038/emm.2017.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61.Mendt MK, Rezvani E, Shpall. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes for clinical use. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2019;54(Suppl 2):789–92. 10.1038/s41409-019-0616-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]