Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent stem cells characterized by their robust proliferative capacity, homing ability, differentiation potential, and low immunogenicity in vitro. MSCs can be isolated from a variety of tissues, primarily including but not limited to bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, placenta, and dental pulp. Although there have been a large number of clinical studies on the treatment of diseases by MSCs and MSCs-derived exosomes (MSCs-EXO), the large-scale clinical application of MSCs and MSCs-EXO have been limited due to the heterogeneity of the results among various studies. This review provides a detailed description of the classification and characterization of MSCs and MSCs-EXO, as well as their extraction methods. Furthermore, this review elaborates on three key mechanisms of MSCs and MSCs-EXO: paracrine mechanisms, immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects, as well as their promotion of tissue regeneration. This review also examines the role of MSCs and MSCs-EXO in cardiovascular diseases, neurological disorders, autoimmune diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, and other systemic diseases over the past five years, while discussing the challenges and difficulties associated with their clinical application. Finally, we systematically summarized and analyzed the potential causes of the various heterogeneous results currently observed. Additionally, we provided an in-depth discussion on the challenges and opportunities associated with the clinical translation of disease treatment approaches based on MSCs, MSCs-EXO, and engineered exosomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

New therapeutic approaches of mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes

Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in clinical trials

Translational potential of mesenchymal stem cells in regenerative therapies for human diseases: challenges and opportunities

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, books and news in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.

Introduction

The concept of stem cell was first proposed in 1868 to describe the properties of fertilized egg [1]. It was identified in murine bone marrow and characterized based on their multilineage differentiation potential [2]. The term of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) was formally introduced and separated in 1991 as a distinct category of stem cells, and has been widely utilized in research and clinical applications since then [3]. MSCs are pluripotent stem cells with the capacity of proliferative and self-renewal, homing, pluripotency and low immunogenicity. MSCs come from a wide range of sources. In addition to bone marrow, they can usually be isolated in adipose tissue, dental pulp, umbilical cord and placenta [4].

In 1967, extracellular vesicles (EVs) secreted by chondrocytes was first observed by E Bonucci [5]. EVs are a class of lipid bilayer particles secreted by cells, which are primarily composed of exosomes (50–150 nm) and micro-vesicles (50–1000 nm) [6]. Exosomes, a subtype of EVs, exhibit a topological structure similar to that of cells [7]. In the 1980s, it was established that the normal synthesis and secretion of exosomes are essential for certain physiological processes [8]. Furthermore, subsequent research has indicated that exosome secretion may play a role in the quality control of specific plasma membrane proteins [9]. An increasing body of research has demonstrated that exosomes can mediate intercellular communication via receptor-ligand interactions, participate in a wide range of cellular processes, and play a significant role in the pathogenesis and progression of various diseases [10,11,12].

In recent years, MSCs and the MSCs-derived exosomes (MSCs-EXO) have demonstrated significant research advances in the treatment of a variety of diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), neurological disorders, autoimmune diseases (ADs), musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and some other diseases. This review will focus on the properties and features of different types of MSCs and MSCs-EXO. In addition, we described the mechanism of MSCs and MSCs-EXO in treating diseases. Moreover, we summarize the recent application of MSCs and MSCs-EXO in the clinical treatment of the aforementioned diseases. Finally, we discuss the current status, limitations and future challenges for the application of MSCs and MSCs-EXO in clinical.

Classification and characterization of MSCs

MSCs, a type of multipotent stromal cells, can adhere to the bottom of the petri dish in cell culture. It can express surface molecules such as CD105, CD73 and CD90, and hardly expresses CD45, CD34, CD14 or CD11b, CD79α or CD19+, HLA-DR+ [13]. Initially, MSCs were predominantly isolated from bone marrow for applications in disease treatment and tissue repair. However, due to the process of bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) is invasive and painful, researchers have gradually shifted the focus to isolating MSCs from other alternative tissues such as adipose tissue, umbilical cord, and dental pulp. According to their sources, MSCs can be classified into the following categories: BM-MSCs, adipose tissue-derived MSCs (AD-MSCs), umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs), placenta-derived MSCs (P-MSCs), dental pulp-derived MSCs (DP-MSCs), and MSCs from other sources [14]. This section will provide a comprehensive overview of the sources, properties, and characteristics of the above common cell types of MSCs.

Bone marrow-derived MSCs

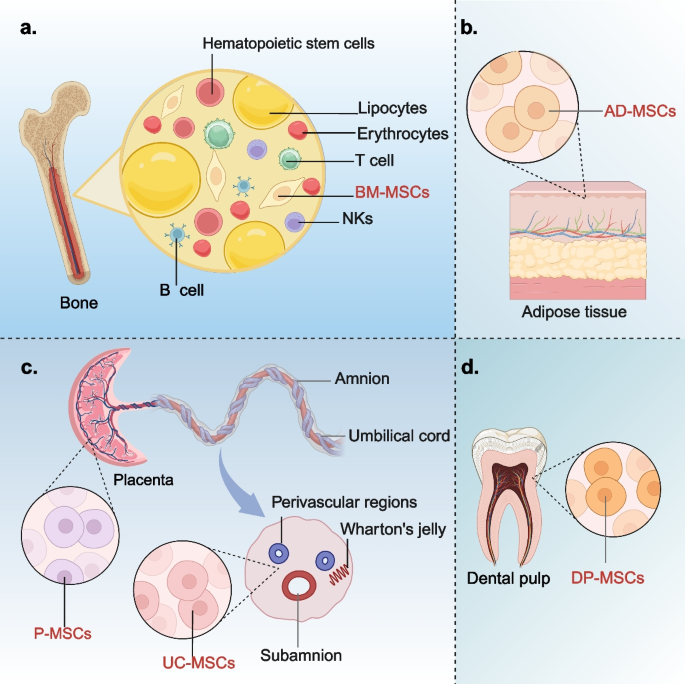

In 1976, Friedenstein et al. [15] initially discovered MSCs in the bone marrow of adult mice and named them fibroblasts precursor cells for the first time, also known as BM-MSCs (Fig. 1a). Although the content of BM-MSCs in bone marrow is very small, BM-MSCs are widely used in the treatment of multiple diseases due to their capacity of rapid proliferation, highly stable genetic characteristics, low immunogenicity and excellent multiline differentiation potential [16,17,18]. The cellular properties of BM-MSCs are usually closely related to the physical health status, pathophysiological status and the age of donor. For example, as donor age increases, indicators of aging in BM-MSCs also rise, which include oxidative damage, the elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the increased expression of p21 and p53 [19]. Consequently, BM-MSCs exhibit enhanced differentiation tendencies. This means that the adaptability and therapeutic effectiveness of BM-MSCs will decline with the increasing of donor ages.

Overview of the classification and characteristics of MSCs. Different types of MSCs are derived from different tissues, mainly from bone marrow (a), adipose tissues (b), umbilical cord and placenta (c), and dental pulp (d). MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells; MSCs-EXO: MSCs-derived exosomes; BM-MSCs: bone marrow-derived MSCs; AD-MSCs: adipose tissue-derived MSCs; UC-MSCs: umbilical cord-derived MSCs; P-MSCs: placenta-derived MSCs; DP-MSCs: dental pulp-derived MSCs

Bone marrow is a complex tissue comprising various cell types. In addition to BM-MSCs, it also contains non-MSCs populations such as hematopoietic stem cells, red blood cells, and various immune-related cells. These diverse cell types collaborate to support hematopoiesis and the immune system. Traditional methods for the isolation and culture of BM-MSCs primarily rely on purification based on intrinsic cellular characteristics, including adhesion time, growth patterns, and tolerance to digestive enzymes during passaging. However, BM-MSCs are not the dominant cell population in the bone marrow. It is hard to develop BM-MSCs into the dominant cell population in the process of isolation and culture. Furthermore, BM-MSCs are frequently co-isolated with other cell types, which poses significant challenges for their purification and subsequent clinical application. In recent years, with the continuous innovation of biological technology, new methods such as density gradient centrifugation, hyaluronic acid hydrogel and flow cytometry have greatly improved the isolation purity of BM-MSCs [20]. These new methods provide a guarantee for further study of the function and clinical application of BM-MSCs. Among the standards established by the International Society for Cell Therapy (ISCT), the three minimal criteria for identifying BM-MSCs are as follows: First, cells must exhibit adherence to plastic substrates. Second, cells must express specific surface antigens, including positivity for CD105, CD73, and CD90, and negativity for CD45, CD34, CD14 or CD11b, and CD79a or CD19. Third, under standardized in vitro culture conditions, these cells must demonstrate the potential to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, or chondrocytes [21].

It is worth mentioning that the separation method of density gradient centrifugation is usually applicable to the separation of liquid cells and can accurately separate BM-MSCs separated from bone marrow cell suspensions. However, it cannot be applied to tissue matrices characterized by solids such as fat or umbilical cord and placenta [22]. Furthermore, compared with the density gradient centrifugation method, directly isolating BM-MSCs from bone marrow by leveraging their characteristic adhesion to culture plastic is a more advantageous approach. This method can significantly enhance the expression level of HLA-DR, which may serve as a potential marker for evaluating the quality control of MSCs in certain contexts [23]. In addition, during the amplification of BM-MSCs, cell density serves as a critical parameter. Specifically, when the cell density in the ranges of T25 culture flask between 10,000 and 100,000 cells/cm2, the expansion rate of MSCs can be significantly enhanced, thereby facilitating large-scale cell culture [24]. After being cultured in vitro for 5 to 7 days, plastic-adherent MSCs may exhibit heterogeneous morphologies resembling fibroblasts, including endothelial cells (ECs), under microscopic observation. During the amplification process, the heterogeneity of adherent MSCs gradually diminishes, with fibroblast-like cells progressively becoming the predominant cell population [21]. The common traditional conditioned medium used for the in vitro culture of BM-MSCs mainly include DMEM/F12, α-MEM and DMEM which supplemented with 10%−15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) [25,26,27]. However, it has been shown that traditional conditioned medium of BM-MSCs can repair damaged tissues and has the characteristics of high immune compatibility, there are still some safety problems such as allergy in clinical application. In this context, FBS is frequently employed as a supplementary component in traditional culture medium for MSCs. But its use may introduce risks of immunogenicity or contamination. In contrast, human platelet lysate (HPL) has been demonstrated to be a safe and efficient alternative to FBS. HPL effectively mitigates the risks of immune reactions and infections associated with FBS, supports robust MSCs expansion, and holds promise as a viable substitute for FBS in MSCs culture [24]. In recent years, the traditional conditioned medium has been progressively supplanted by emerging serum-free conditioned medium. Compared with the traditional conditioned medium, serum-free conditioned medium can better expand BM-MSCs in vitro, maintain the pluripotency of BM-MSCs, and shorten the culture cycle [28]. This provides a safe guarantee for the clinical application of BM-MSCs.

Adipose tissue-derived MSCs

AD-MSCs are pluripotent stem cells derived from adipose tissues with the potential to differentiate into various cell lineages (Fig. 1b). More than 90% of the surface antigens on the cell membrane of AD-MSCs are identical with BM-MSCs [29, 30]. Compared to BM-MSCs, AD-MSCs have a broader range of tissue sources. Additionally, the yield of MSCs from adipose tissue is significantly higher than that from bone marrow, and the quantity of AD-MSCs obtained in a single extraction is sufficient to meet the requirements of clinical applications [31]. It can be speculated that the use of freshly isolated cells is likely to be safer compared to cells subjected to in vitro culture and secondary expansion. This is due to the fact that during prolonged in vitro culture, cumulative genetic and epigenetic alterations may occur, potentially affecting cellular function and biological properties [32]. BM-MSCs extraction from bone marrow is a painful process, which often puts stress on the donor. However, the extraction of AD-MSCs from adipose tissue is less psychologically stressful for the donor and more acceptable. Therefore, this also increases the motivation for donors to donate AD-MSCs. Compared with BM-MSCs, AD-MSCs have more stable morphological and genetic characteristics, higher proliferative activity and lower senescence rate under the same in vitro culture conditions [33, 34]. Unlike the isolation of BM-MSCs, the isolation of AD-MSCs necessitates the use of digestive enzymes to separate AD-MSCs from the surrounding fascia, adipocytes, and vascular ECs [35]. Consequently, the process of isolating AD-MSCs demands precise control over the duration of enzymatic digestion to prevent significant adverse effects on cell viability and reparative capacity.

Umbilical cord-derived and placenta-derived MSCs

In the 1990 s, UC-MSCs were first isolated from connective tissue [36]. The current study shows that UC-MSCs are isolated from four main sites in the umbilical cord: Wharton’s jelly, perivascular regions, subamnion and amnion. Wharton’s jelly region is the main source regions of UC-MSCs (Fig. 1c) [37]. Li et al. compared MSCs from four different sources and found that UC-MSCs from Wharton’s jelly proliferate the fastest which are easy to be isolated and culture, and can maintain the characteristics through multiple generations in vitro [38]. In addition, UC-MSCs express almost no MHC II antigens associated with homoimmune rejection and have undergone barely any cellular ageing [39]. Therefore, compared with adult MSCs, UC-MSCs exhibit lower immunogenicity, non-tumorigenicity, decreased heterogeneity, and enhanced pluripotency. [40]. This means that UC-MSCs have better clinical application potential than adult MSCs. In vitro, The isolation and culture of UC-MSCs can be obtained not only by enzymolysis of collagenase, hyaluronidase or other proteases, but also by explants. UC-MSCs are easy to proliferate and culture, and no ethical concerns about their collection [41, 42]. Compared with UC-MSCs obtained by enzymatic hydrolysis, the number of UC-MSCs obtained from explants was higher due to the significant up-regulation of mitosis and cell cycle related gene expression in acquired cells [43]. These results indicate that enzymatic hydrolysis technology has certain limitations due to its ability to destroy cell surface structures and proteins and reduce cell viability. Explants culture is a milder technique for the isolation and culture of UC-MSCs than enzymatic hydrolysis.

Consistent with the umbilical cord, the placenta also originates from mesenchymal tissue during embryonic development and shares a similar developmental biological background [44]. Therefore, whether it is UC-MSCs or P-MSCs (Fig. 1c), they all have similar immunomodulatory characteristics, low immunogenicity, and consistency in cell morphology [45]. However, owing to the complexity of the placental tissue structure, this typically entails that when preparing P-MSCs, more sophisticated isolation and purification procedures are required to achieve P-MSCs with higher purity [46].

Dental pulp-derived MSCs

In recent years, DP-MSCs, as an alternative cell source, have demonstrated significant therapeutic potential and have garnered increasing attention from researchers. DP-MSCs are a unique pluripotent cell population with significant mesenchymal characteristics [47]. Different from the origin of BM-MSCs and AD-MSCs, DP-MSCs are mainly derived from the embryonic layer of neural crest and have certain neurophilic characteristics (Fig. 1d) [48]. It is easily isolated and obtained from human third molars removed for orthodontic reasons, and can also be isolated and extracted from the pulp of animals (including dogs) [49]. The abundant cell supply and painless stem cells collection method of DP-MSCs make them a rich source of cells for regenerative medicine with less risk of complications. In addition, DP-MSCs also have advantages such as high proliferation capacity, good differentiation potential, favorable paracrine, minimal invasion, and immune regulation [50]. As a mesenchymal cell population in dental pulp, DP-MSCs have stem cells’ properties expressed by specific markers [51]. In a preclinical study, DP-MSCs were found to express embryonic stem cell markers such as SKIL, MEIS1, and JARID [52]. This suggested that DP-MSCs have the same immunomodulatory and regenerative characteristics as embryonic stem cells. However, there are still other cells in the pulp, such as fibroblasts, highly differentiated dentin-forming odontoblasts, mesenchymal progenitor cells, and perivascular cells. When isolating DP-MSCs, surface markers for positive characterization of MSCs (primarily CD73, CD90, and CD105) are commonly shared with these cells [21]. The detection of a single marker is insufficient to determine the purity of DP-MSCs, and multiparameter flow cytometry addresses this limitation by simultaneously detecting multiple molecular markers [51]. Colony separation is a cell isolation technique that distinguishes the proliferative and self-renewal capacities of stem cells based on cell surface markers, as well as the size and morphology of colonies formed during cell culture. This method is primarily used to isolate DP-MSCs with distinct mesenchymal surface markers; however, it is not suitable for obtaining homogeneous populations of DP-MSCs [53]. Homogeneous populations of DP-MSCs may express similar or identical surface markers, and may have a high degree of morphological and functional consistency during cell culture [54]. When cultured under 3D conditions that more closely mimic the in vivo environment, DP-MSCs can better preserve their original properties, in contrast to the conventional 2D culture environment typically used in standard cell culture dishes [55]. The difference of cell culture density has different effects on the maintenance of stem cell characteristics. The confluent culture condition had a negative effect on the maintenance of stem cell characteristics, while the sparse culture condition had the opposite effect [56]. However, in the densely cultured DP-MSCs, the expression of PI3 K was upregulated [55]. PI3 K catalyzes the intracellular conversion of PIP2 to PIP3. PIP3 recruits AKT to the cell membrane and promotes its activation. Activated AKT can affect the differentiation direction of DP-MSCs and promote their proliferation [57]. Perhaps when DP-MSCs are used for some tissue regeneration, confluent culture may be an alternative strategy.

Other sources

In recent years, researchers have gradually discovered that MSCs can be successfully isolated from other tissues such as the endometrium [58], peripheral blood [59], ectodermal tissues (such as keratin of the cornea, [60] skin and accessory organs of the eye [61]), skeletal muscle and muscle [59, 62], venous vessels [62], peripheral blood [63] and the fetus including the heart, intestinal epithelium and dermal tissue [64]. However, these tissues do not have a stable source. Ethically, it is also not suitable as a tissue source for large-scale clinical production of MSCs.

Exosomes and MSCs-derived exosomes

Characterization and isolation of exosomes

Exosomes are small membrane-bound vesicles of endocytic origin, which can be produced by nearly all organisms and cell types [65]. Specific proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, and glycoconjugates formed the structure of exosomes [66]. In less than five decades since their discovery, exosomes have emerged as a significant research focus due to their advantages such as high safety, easy preservation and transportation, no ethical controversy, and obvious therapeutic effect. Currently, the extraction methods of exosomes mainly include differential ultracentrifugation, ultrafiltration, size-exclusion chromatography, polymer precipitation, microfluidics and immunoaffinity capture. Among these, the gradient ultrafast centrifugation is the most common extraction method [67]. This technique involves the sequential application of increasing centrifugal forces to separate exosomes from other cellular components based on their buoyant densities. The process typically involves multiple rounds of centrifugation, yielding purified exosomes in the final pellet [68]. However, this method comes with several drawbacks, including the high cost of equipment, the time-consuming nature of the process, and the instability in the number of exosomes obtained. In recent years, the method of polymerization-induced precipitation has gained considerable popularity among researchers due to its cost-effectiveness and high yield, and has emerged as a viable alternative, gradually becoming the second choice for exosome extraction, as evident in various studies [69]. The principle of polymerization-induced precipitation is similar to Ethanol-mediated nucleic acid precipitation which forms a hydrophobic microenvironment through the interaction of highly hydrophilic polymers with water molecules around exosomes. This causes the exosomes to precipitate [70]. However, compared with differential ultracentrifugation, this method can lead to non-specific protein contamination and may influence the analysis of downstream results [71]. For exosomes that have been subjected to extraction and purification, a comprehensive quality assessment is typically performed from the perspectives of particle size distribution, quantification, and biological activity. When performing quality assessment, a range of advanced techniques can be employed, such as nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) [72], transmission electron microscopy (TEM) [73], atomic force microscopy (AFM) [74], and Western blotting [74]. These techniques not only enable precise evaluation of the size distribution, morphological characteristics, purity level, and protein composition of exosomes but also ensure that the extracted exosomes comply with the anticipated quality and purity standards. Moreover, exosomes demonstrate remarkable resilience to various storage conditions. They can be preserved under freezing conditions or via freeze-drying technology, which substantially decreases costs associated with manufacturing, storage, and transportation [74]. Therefore, selecting an appropriate exosome extraction method, as well as quality control and storage approaches, is of particular importance for ensuring the accuracy of subsequent experimental results.

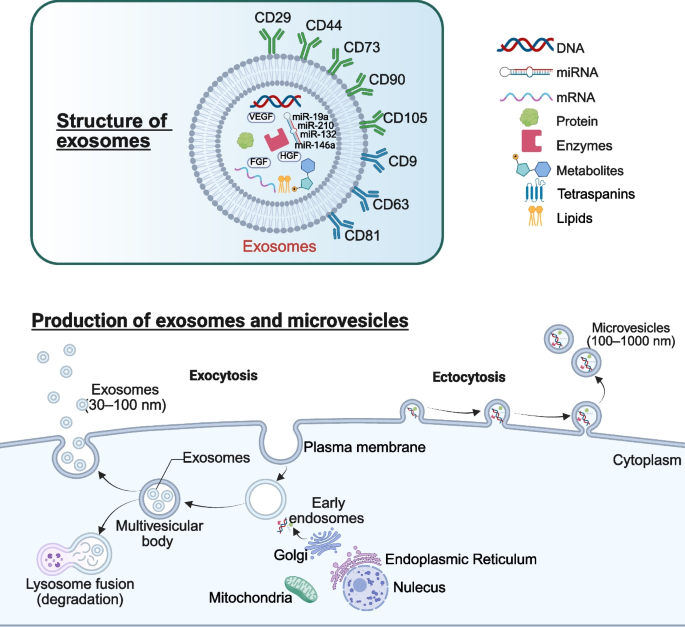

Roles of exosomes in cell communication

The production process of exosomes primarily involves several key steps: the formation of the plasma membrane, the sorting of endosomes and multivesicular bodies, and the release of exosomes through the fusion of multivesicular bodies with the plasma membrane [75]. During the biogenesis of exosomes, various substances, including nucleic acids (miRNA, long non-coding RNA, circRNA, and DNA), proteins, lipids, and even mitochondria, are encapsulated and subsequently delivered to target cells [76]. MiRNAs, as one of the key molecular cargos delivered by exosomes, are initially transcribed into primary miRNAs in the nucleus. These primary miRNAs are subsequently processed by the Drosha enzyme to generate precursor miRNAs, which are then transported to the cytoplasm via Exportin-5. In the cytoplasm, these precursors are further processed into mature miRNAs. During exosome biogenesis, mature miRNAs can associate with RNA-induced silencing complexes (RISCs) and subsequently be encapsulated within exosomes, thereby becoming functional components of these EVs [77]. MiRNAs not only protect exosomes from enzymatic degradation during delivery but also facilitate their transfer to target cells via endocytosis or by binding to specific receptors. Additionally, miRNAs can bind to the 3’UTR region of target-cell mRNA, thereby inhibiting translation or inducing degradation and consequently modulating the expression of downstream genes [78].

Mitochondria, as important organelles within cells, can regulate energy metabolism, apoptosis and cell signal transduction. The transcellular transfer of mitochondria is the key mechanism to ensure the smooth execution of its functions. Exosomes, as one of the microtubule cytoskeletons with common intracellular movement patterns, can provide significant impetus for the transport complexes on the cytoskeleton to drive mitochondrial movement [79]. Under the stimulation of energy stimulation, oxidative stress or DNA damage, the intracellular ROS level increases, and exosomes can achieve mitochondrial transcellular transfer. Research has found that astrocytes can release a large number of exosomes containing mitochondria under the conditions of stimulating ischemic stroke in vivo and excreting serum in vitro, reducing peripheral nerve damage [80]. In a mouse model of lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury, exosome-mediated functional mitochondrial transfer can promote anti-inflammatory and antioxidant stress in mouse macrophages [81]. As a transmembrane protein, the NAD +/CD38/cADPR/Ca2+ pathway mediated by CD38 is the key to exosome-mediated mitochondrial transcellular transport. This pathway can not only be involved in the endocytosis stage of exosomes, but also in the exocytosis stage, influencing intercellular communication and material exchange [82]. The inhibition of endocytosis will lead to a reduction in mitochondrial transfer from BM-MSCs to damaged alveolar epithelial cells. Furthermore, Connexin 43 (CX43), as a connexin of mitochondria, the interstitial junction channels it mediates can significantly enhance the efficiency of mitochondrial transcellular transfer. Under certain conditions, it can protect myocardial and brain tissues from ischemia–reperfusion injury and is involved in the endocytosis of reticin-dependent exosomes [83].

Exosomes are secreted from parent cells and their targeting mechanisms remain incompletely understood. Research has demonstrated that exosomes can be internalized by recipient cells through protein–protein interactions (such as fusion with the plasma membrane and direct interaction with surface receptors) or receptor-ligand interactions (including caveolae-dependent or caveolae-independent endocytosis), thereby performing their functional roles [84]. In the first way, integrins, tetraspanins, and other adhesion proteins play a crucial role in exosome targeting and the selective uptake by recipient cells [85]. Integrins are cell adhesion molecules that play an indispensable role in regulating cell growth and function. Targeting integrins α6β4 and αvβ5 can reduce the uptake of exosomes by lung-tropic and liver-tropic tumor cells, thereby decreasing metastasis to the lung and liver, respectively [86]. Connexins are another class of tetraspanins that facilitate intercellular communication on exosome membranes, in addition to integrins. Connexins are primarily composed of two extracellular loops and one cytoplasmic loop, enabling their biological functions through connexin-integrin cross-talk. Notably, CX43, a key member of the connexin family, plays a significant role in regulating exosome release and molecular transfer [87, 88]. CD81, CD9, and CD63 were initially identified as tetraspanin markers of exosomes. However, subsequent research revealed that only CD63 is a specific protein marker for exosomes, whereas CD9 and CD81 are not [89]. Moreover, recent studies have shown that in certain cell types, the absence of these three proteins has minimal impact on the protein composition of exosomes [90]. Previous studies have demonstrated that inhibiting endocytosis in recipient cells can reduce their uptake of exosomes. However, the relationship between endocytosis and exosome release within the same cell remains undetermined. Recent research indicates that endocytosis can inhibit the secretion of vesicular exosome marker proteins (CD81, CD9, and CD63). Additionally, endocytosis can trigger the degradation of exosomes containing CD9 and CD81 [91]. This suggests that cells can either primarily release exosomes as parent cells or simultaneously receive exosomes. This finding provides valuable insights for future research on the production and modification of post-therapeutic exosomes. Exosomes, as secretory vesicles, can be utilized by adjacent cells to exert their functions. For instance, after entering the bloodstream, exosomes can be transported over long distances to reach lesion sites and deliver therapeutic effects. However, hepatic accumulation of exosomes can diminish their therapeutic efficacy [92]. Therefore, engineering exosomes holds significant potential for enhancing their therapeutic performance. Currently, researchers have demonstrated that blocking Scavenger Receptor Class A (a novel monocyte/macrophage uptake receptor for EVs) with dextran sulfate significantly reduces the clearance of EVs in the liver [93]. This finding is crucial for enhancing the effective utilization of exosomes.

MSCs-derived exosomes

MSCs can secrete a lot of secretomes, including cytokines, growth factors and chemokines, and extracellular nanoparticles dominated by exosomes [48]. Compared to the challenges of iatrogenic tumorigenesis, immune rejection, vascular blockage, and ethical concerns faced by MSCs in clinical applications, MSCs-EXO not only effectively mitigate these issues but also exhibit comparable reparative effects to those of MSCs [94]. MSCs-EXO carry not only the characteristic markers of MSCs (such as CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, and CD105), but also the characteristic markers of exosomes (such as CD9, CD63, and CD81) [95]. MSCs-EXO primarily exerts its functions by transferring various bioactive molecules, including growth factors (such as VEGF, FGF, HGF), anti-inflammatory proteins, anti-apoptotic proteins, cell survival-promoting factors, angiogenic proteins, microRNAs (such as miR-19a, miR-132, miR-146a, miR-210), long non-coding RNAs, circRNAs, mRNAs, and lipids (Fig. 2) [76, 96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104]. This is usually achieved by the target cell internalizing MSCs-EXO into the cell through endocytosis. After the proteomics analysis of AD-MSCs-derived exosomes (AD-MSCs-EXO), BM-MSCs-derived exosomes (BM-MSCs-EXO), UC-MSCs-derived exosomes (UC-MSCs-EXO) and DP-MSCs-derived exosomes (DP-MSCs-EXO). Zheng-Gang Wang et al. found 771, 457 and 431 proteins respectively, 355 of which were common proteins [105]. This study indirectly suggests that different MSCs-EXO may have different therapeutic effects on the same disease. In addition, miRNA is also an important component of MSCs-EXO and plays an important role in the treatment of various diseases [106,107,108]. The types and amounts of proteins and miRNAs in MSCs change with the aging of MSCs [109, 110]. Therefore, it can be speculated that the contents of MSCs-EXO will also change with the aging of MSCs, and the cell viability of MSCs will directly affect the therapeutic effect of MSCs-EXO.

Overview of the characteristics and formation process of exosomes. The formation process of exosomes mainly includes: the formation of plasma membrane, the sorting endosomes and multivesicular body and the release of exosomes by the combination of multivesicular body and plasma membrane

Mechanisms Underlying the Therapeutic Effects of MSCs and MSCs-EXO

Paracrine Signaling

Paracrine pathway is considered to be the primary pathway for stem cell therapy. In a narrow sense, paracrine factors with diameters less than 10 nm secreted by stem cells are referred to as paracrine substances, and the term paracrine encompasses all secretory products, including exosomes and other cellular vesicles in a broader context [111]. Extensive research has demonstrated that stem cells secrete a wide array of bioactive molecules, such as anti-inflammatory factors, growth factors, cytokines, and specific active factors [112, 113]. These secretomes play crucial roles in regulating stem cell homing, enhancing self-survival, promoting anti-apoptotic effects, stimulating angiogenesis, modulating immune responses, inhibiting excessive fibrosis, and facilitating cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation [114, 115].

The conditioned medium from stem cells demonstrates a therapeutic efficacy comparable to that of stem cells themselves, providing robust evidence that the paracrine mechanism plays a crucial role in the disease-treating effects of stem cells. For instance, the conditioned medium from DP-MSCs not only alleviates cardiomyocyte apoptosis in ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) mouse models but also inhibits I/R-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vitro [116]. For AD-MSCs, their conditioned medium could attenuate I/R-induced cardiac injury through the microRNA-221/222/PUMA/ETS-1 pathway [117]. In addition, conditioned medium from AD-MSCs could also protect neuronal and oligodendroglia cells exposed to oxygen–glucose deprivation (OGD) [118]. It is well established that external stimuli enhance the paracrine activity of MSCs, offering valuable insights for leveraging this property in disease treatment. Therefore, hypoxia [119], ischemia [120], carbon monoxide exposure [121], physical factors [122], beneficial chemical elements [123], cytokines [124], and pharmacological agents [125] can be employed to enhance the paracrine effect and efficacy of MSCs. For example, under ischemic conditions, MSCs can mitigate cardiomyocyte apoptosis by secreting exosomes enriched with miR-22 [126, 127]. Compared with UC-MSCs in normal oxygen environment, hypoxia-preconditioned UC-MSCs have better angiogenesis in the treatment of myocardial infarction (MI) mice. Furthermore, the latter conditioned medium can better promote the formation of human umbilical vein EC tubules in vitro [128]. In the osteochondral defect model, hypoxia-preconditioned BM-MSCs facilitate cartilage regeneration and attenuate joint inflammation through the mediation of EVs [129]. MSCs pretreated with metformin can enhance their proliferative capacity and activity by augmenting their paracrine effects, thereby mitigating inflammation and fibrosis in chronic kidney disease (CKD) models [130].

The combination of MSCs with gene editing technology, or the integration of MSCs with other therapeutic modalities, represents another important strategy for enhancing paracrine activity. For example, the genes associated with hypoxia resistance and enhanced migration, including HIF-1α [131], SDF-1 [132], HO-1 [133], CXCR4 [134], and specific miRNAs [135,136,137], were transferred into MSCs through gene editing technology could improve the repair ability of MSCs. The combination of pharmacological agents, physical factors, and novel polymeric materials with MSCs can improve therapeutic efficacy and augment immune modulation [138,139,140,141,142]. Although the synergistic mechanisms underlying combination therapy have not been fully elucidated, several studies suggest that they may be associated with enhanced paracrine effects of MSCs [143, 144]. Therefore, actively elucidating the mechanisms by which combination therapy achieves a synergistic effect on paracrine signaling will be a key focus of future research.

Immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory

Innate immunity is an important part of immune response. Cells involved in innate immunity primarily include neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells (DCs), as well as specific lymphocyte populations such as natural killer (NK) cells and γδ T cells. These cells secrete inflammatory mediators like ROS, IL-6, and TNF-α in response to various exogenous and endogenous stimuli, thereby inducing an inflammatory response [145].

Within the first few hours following tissue damage, innate immune responses will gradually be initiated. During this process, in addition to growth factors, chemokines, and pro-fibrotic factors, the damaged tissues can also release a large number of inflammatory factors. The change of microenvironment and the accumulation of inflammatory factors can lead to the increase of vascular permeability and drive inflammatory cells to gather at the damaged area [146]. Various pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines released by activated macrophages co-create a pro-inflammatory environment with cytokines released by damaged tissue. This pro-inflammatory environment attracts neutrophils to the damaged area to participate in early inflammatory responses. This process usually occurs within 6 h after tissue damage [147]. Adaptive immunity, primarily mediated by B and T lymphocytes, enables the recognition of specific pathogens and the generation of pathogen-specific antibodies. For example, in the treatment of malignant tumor diseases, MSCs can stimulate central granulocytes to secrete IL-10 and PGE2, thereby inhibiting the proliferation of T lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment [148]. This immune response plays a crucial regulatory role in the pathogenesis and progression of diseases such as atherosclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), cancer and osteoarthritis (OA) [148,149,150,151,152].

The immune response can both inflict damage on tissues and trigger the wound healing process, including the formation of scar tissue [153]. Therefore, there exists a delicate balance between the damaging and reparative effects during the inflammatory response. If this balance is disrupted, it can lead to either an excessive inflammatory response or inadequate repair of tissue damage. Consequently, maintaining the equilibrium between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses is essential for optimizing the protective effect on injured cells. For example, on the first day after myocardial damage, the activated M1 macrophages and their secreted cytokines, together with attracted neutrophils, create a more intense pro-inflammatory environment. More immune cells are attracted and additional damage is caused to cardiomyocytes [147]. However, macrophages can also change from M1 type to M2 type, and the cytokines secreted by M2 type macrophages are mainly anti-inflammatory, wound healing and angiogenesis [154]. This is crucial for the protection and preservation of damaged cardiomyocytes. In recent years, a substantial body of research has elucidated the significant role of MSCs and MSCs-EXO in immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory across various diseases, including MSDs, CVDs, neurological disorders, ADs, and others.

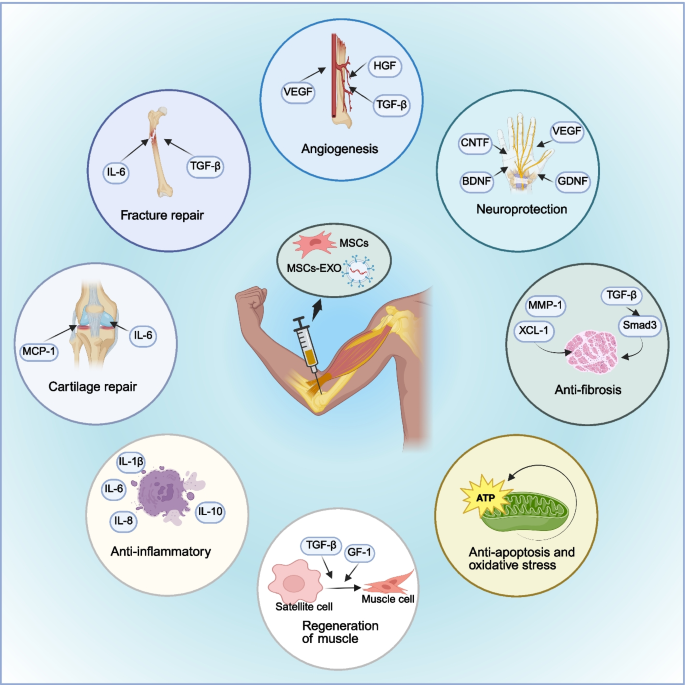

OA is a representative disease of MSDs. It is a complex, multifactorial degenerative condition that arises from the interplay of biomechanical factors and inflammatory processes. MSCs and MSCs-EXO can attenuate the activity of pro-inflammatory immune cells and modulate local and systemic biomarkers, thereby regulating the immune response in OA (Fig. 3) [155]. Mitochondria are key organelles in oxidative stress. Mitochondria derived from MSCs can reverse abnormalities in energy metabolism and mitochondrial dynamics in chondrocytes in OA, thereby enhancing chondrocytes’resistance to oxidative stress and apoptosis [156]. In addition, MSCs-EXO can alleviate cartilage degradation and synovial inflammation in OA through ferroptosis [157]. Furthermore, the synergistic integration of biological scaffolds composed of polymer materials with MSCs can augment their anti-inflammatory effects in the OA microenvironment [158, 159].

Application of MSCs and MSCs-EXO in MSDs. MSCs and MSCs-EXO are primarily administered via intra-articular injection to the affected site, exerting therapeutic effects such as fracture repair, cartilage regeneration, anti-inflammatory responses, muscle regeneration, anti-apoptosis, oxidative stress reduction, anti-fibrosis, neuroprotection, and angiogenesis for the treatment of musculoskeletal diseases. MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells; MSCs-EXO: MSCs-derived exosomes; MSDs: musculoskeletal disorders

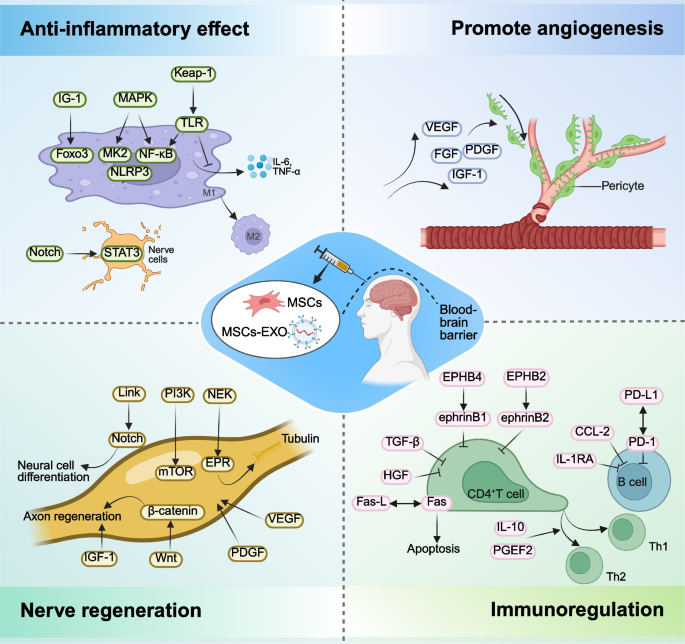

Neurological disorders are frequently associated with neuroinflammation (Fig. 4). Neuroinflammation is activated by damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [160]. Upon damage to neurons and glial cells, the DAMPs secreted by these cells can activate microglia and astrocytes, leading to changes in their morphology and function [161]. Microglia and astrocytes serve as the primary effector cells of the innate immune response in the central nervous system. Their activation subsequently enables these cells to exert their immunomodulatory effects. Similar to macrophages, activated microglia exhibit two distinct phenotypes: M1 and M2. The M1 phenotype is primarily associated with pro-inflammatory responses, whereas the M2 phenotype is predominantly involved in anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective functions [162]. Astrocytes can also produce pro-inflammatory or immunomodulatory mediators depending on their polarization phenotype [163]. MSCs represent an ideal cell source for neural reparation and inflammation reduction due to their low immunogenicity and paracrine effects. MSCs primarily modulate neuroinflammation through their interactions with microglia and astrocytes. For example, MSCs-EXO can inhibit inflammation and promote the recovery of neurological function by entering microglia and suppressing their activation [164]. Furthermore, MSCs-EXO enriched in miR-216a-5p can also regulate microglial polarization by modulating the TLR4/NF-κB/PI3 K/AKT signaling pathway [165]. GFAP and IBA1 serve as markers for astrocytes and microglia, respectively. Exosome therapy can significantly reduce the transcription levels of inflammatory markers in astrocytes and microglia, indicating a diminished inflammatory state following spinal cord injury (SCI) [166]. Post-stroke inflammatory injury is a critical factor that exacerbates stroke-induced brain damage. MSCs overexpressing HO-1 exhibit a significant therapeutic effect on hyperinflammatory injury following stroke in mice, ultimately promoting recovery after ischemic stroke [167].

Application of MSCs and MSCs-EXO in neurological disorders. MSCs and MSCs-EXO can exert therapeutic effects by reducing inflammation, promoting angiogenesis, facilitating nerve regeneration, and modulating immune responses. MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells; MSCs-EXO: MSCs-derived exosomes

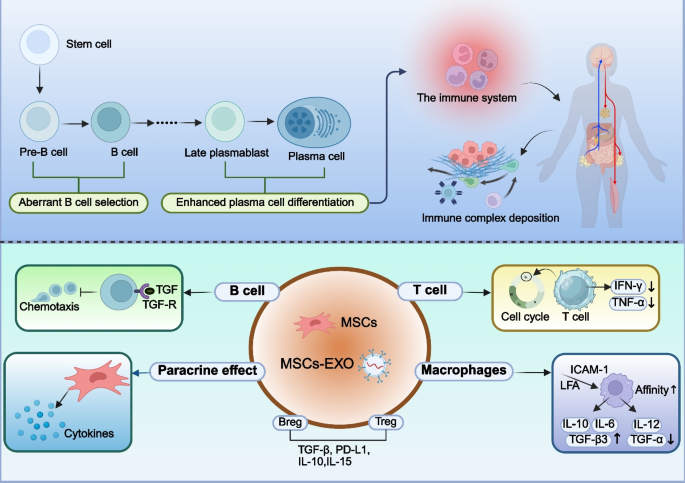

ADs comprise a group of chronic inflammatory disorders characterized by the immune system attacking the body’s own tissues, leading to the formation and deposition of immune complexes [168]. MSCs and MSCs-EXO can elicit either inhibitory or stimulatory immune responses, thereby participating in immune regulation and modulation. The aberrant expression of autoantibodies is a key mechanism underlying the occurrence and development of AD, and the emergence of these autoantibodies is frequently attributed to aberrant B cell selection or enhanced plasma cell differentiation, indicating a breakdown in self-tolerance (Fig. 5) [169]. MSCs and MSCs-EXO contribute to the treatment of AD by modulating the aberrant expression of autoantibodies [170]. BM-MSCs can inhibit antigen-dependent proliferation and differentiation into plasma cells of follicular and marginal zone B cells in SLE mice via the IFN-γ and PD-1/PD-L1 pathways, thereby contributing to the prevention of glomerular damage [171].

Application of MSCs and MSCs-EXO in ADs. ADs primarily arise from aberrant B cell selection and enhanced plasma cell differentiation, leading to the immune system attacking normal human tissues. This results in the deposition of immune complexes. MSCs can inhibit the proliferation of B cells, T cells, and macrophages, promote the release of anti-inflammatory factors, and reduce the production of pro-inflammatory factors. Furthermore, MSCs facilitate the differentiation of T cells and B cells into regulatory subsets, such as Tregs and Bregs. ADs: autoimmune disease; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells; MSCs-EXO: MSCs-derived exosomes; Treg: regulatory T cells; Breg: regulatory B cells

CD4 + T cells also play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of multiple AD, contributing to target organ damage through the production of cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4, IL-17, IL-21, and IL-23 [171, 172]. For example, MSCs can promote the expression of IL-10, downregulate the expression of IL-18 and Th17 cells, thereby correcting the Th17/Treg (a type of CD4 + T) imbalance to exert immunomodulatory effects [173]. Currently, glucocorticoids serve as the cornerstone therapy for the treatment of most AD. Dexamethasone-integrated MSCs and MSCs-EXO can treat SLE by inhibiting the release of IFN-γ and TNF-α from CD4 + T cells and upregulating the expression of CRISPLD2 [174]. Moreover, Dexamethasone-integrated MSC-based biomimetic liposomes enhance their affinity for polarized macrophages via the LFA-1/ICAM-1 interaction, thereby improving the therapeutic efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [175].

In ischemic heart disease, MSCs can reduce the production of inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. This finding further demonstrates the potential therapeutic value of MSCs in cardiac repair [176]. In addition, MSCs-EXO carried by specific miRNA may play a regulatory role in the development of inflammation after MI [177, 178]. These anti-inflammatory effects are mainly achieved through the paracrine mechanisms of MSCs and MSCs-EXO [179]. For example, AD-MSCs-EXO carrying miR-93-5p may prevent myocardial damage by inhibiting TLR4-mediated inflammatory responses [180]. Zilun et al. showed that MSCs-EXO carrying miR-181a inhibited c-FOS protein through cell targeting properties and the immunosuppressive effect of miR-81a, thus inhibiting inflammatory response [181]. Neutrophils are inflammatory cells that accumulate in the border area early after MI, so it is essential to investigate the relationship between MSCs and them. Although some studies have shown that BM-MSCs activated by TLR3 and TLR4 in vitro can reduce neutrophil apoptosis through the combined action of IL-6, IL-β and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor [182]. This does not fully explain why MSCs can inhibit the inflammatory response after myocardial damage. At present, the mainstream view is that MSCs can play a role by inhibiting the activity of neutrophils and accelerating their apoptosis. For example, Dongsheng Jiang et al. suggested that MSCs could phagocytic ICAM1-dependent neutrophils, resulting in a decrease in the number of neutrophils [183]. Other studies have shown that MSCs-EXO can inhibit the excessive spread of inflammation by inhibiting the overactivity of neutrophils [184]. Moreover, the conditioned medium of MSCs have also been found to induce neutrophil apoptosis in vitro [185]. Macrophages are one of the important immune cells that regulate the occurrence and development of inflammation after myocardial damage. Studies have shown that MSCs can accelerate the transformation of M1 macrophages into M2 macrophages in infarct myocardium, it can achieve the purpose of modulating the immunologic environment, accelerating regeneration and inhibiting inflammation [186]. In addition, specifically genetically modified or upregulated MSCs and MSCs-EXO can the duration of inflammation and reduce cardiomyocyte damage by promoting transformation between macrophage subtypes [187, 188]. In summary, it is of great significance to explore how MSCs and MSCs-EXO promote the transformation of M1 macrophages to M2 macrophages and further find the balance between anti-inflammatory and pro- inflammatory.

Promotion of Tissue Regeneration

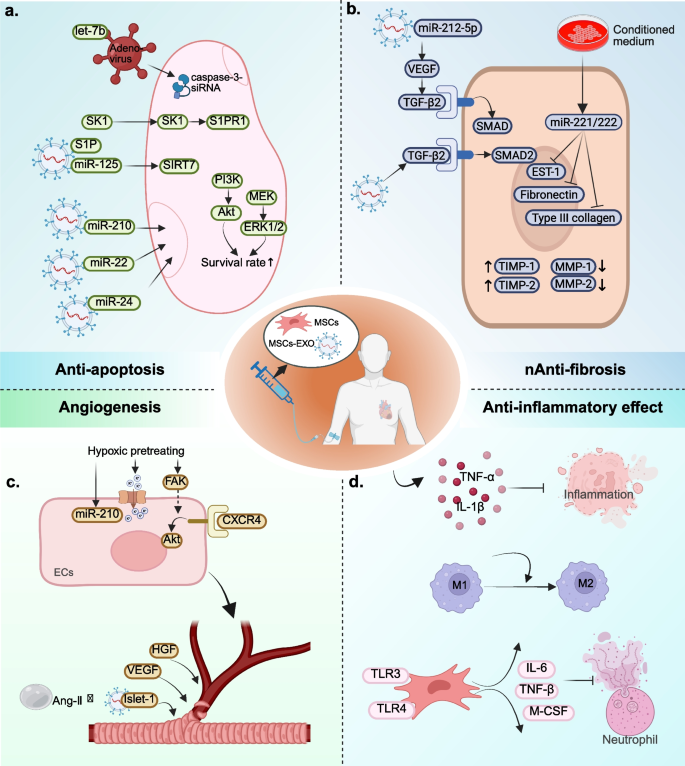

Inhibition of apoptosis, promotion of angiogenesis, targeted differentiation into damaged tissues, and suppression of excessive inflammation constitute four key mechanisms that facilitate tissue regeneration (Fig. 6).

Application of MSCs and MSCs-EXO in MI. a Overview of anti-apoptotic of MSCs and MSCs-EXO; b Overview of anti-fibrosis of MSCs and MSCs-EXO; c Overview of angiogenesis of MSCs and MSCs-EXO; d Overview of anti-inflammatory effect of MSCs and MSCs-EXO. MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells; MSCs-EXO: MSCs-derived exosomes; MI: myocardial infarction

Apoptosis is a complex biological process, and the majority of the mechanisms underlying apoptosis involve a specific type of intracellular enzyme known as the cysteine aspartic acid specific protease (caspase) [189]. The Caspase cascade system plays a crucial role in the induction, transduction and amplification of apoptosis signals within cells. Its activation and function are tightly regulated by a variety of protein molecules and ions including apoptosis inhibitor proteins, Bcl-2 family proteins, calpain, and Ca2+ [190]. At least 7 of the 14 known caspases proteins play a direct role in regulating apoptosis in mammals, while others can also indirectly influence cell death through inflammatory response [191]. Using MI as an example, previous studies have shown that the application of non-selective caspase inhibitors can protect cardiomyocytes from fatal I/R damage in the early stage of MI [192]. Of these known proteins, the activation of caspase-3 is the most crucial in regulating apoptosis following MI. The activation of caspase-3 and the increase of cardiac natriuretic peptides in serum can be detected in non-infarcted areas 1 day after MI and can sustain for up to 4 weeks. At the same time, the Bcl-2/Bax ratio shifted in the direction of pro-apoptotic Bax direction [193]. Chandrashekhar et al. also obtained similar research results through experiments [194]. This suggested that heart failure (HF) may occur in the early stage of MI. Using caspase-3-siRNA to intervene in caspase-3 expression in acute MI (AMI) mice can significantly reduce infarct size and decrease the apoptotic index. Additionally, it improves ventricular function in AMI mice [195]. MSCs transduced with adenovirus-mediated human tissue kallikrein gene can enhance their resistance to hypoxia-induced apoptosis and decrease caspase-3 activity. Moreover, treatment of AMI mice with these cells can improve ventricular function, reduce infarct size, attenuate ventricular remodeling, and promote angiogenesis [196]. Ham et al. found that, compared with conventionally cultured MSCs, mice treated with let-7b-transfected MSCs exhibited improved left ventricular function and increased microvascular density. This effect is achieved by protecting the transplanted MSCs from apoptosis and autophagy through direct targeting of the caspase-3 signaling pathway by let-7b [197]. These studies indicate that MSCs can reduce cardiomyocyte apoptosis after MI by decreasing the activity of caspase-3.

Not only MSCs have anti-apoptotic effect, but MSCs-EXO can also reduce the oxidative stress after MI and improve the anti-apoptotic ability of cardiomyocytes in the peri-infarction area. Regardless of the choice of intramuscular injection [198, 199], intra-coronary injection [200], intravenous injection (IT) [201, 202] or intracardiac injection [203], MSCs-EXO can play a role in reducing the apoptosis of endogenous cardiomyocytes. Pretreated or genetically modified MSCs-EXO have better anti-apoptotic ability than untreaded or unmodified MSCs-EXO. For example, MSCs under anoxia can release exosomes enriched with miR-210 and reduce cardiomyocyte apoptosis after MI [204]. MSCs-EXO can ameliorate myocardial injury and reduce apoptosis after MI by activating S1P/SK1/S1PR1 signaling and promoting M2 macrophage transformation [205]. Zhang et al. [206] also showed that the miR-24 released level of BM-MSCs-EXO hypoxic preconditioning was significantly higher than that of normal-oxygen pretreating of BM-MSCs. After the injection of hypoxic BM-MSCs-EXO, the level of miR-24 in AMI mice showed significant differences. The MI size was reduced and the left ventricular function improved. Other studies have shown that genetically modified MSCs-EXO with miR-125b can target SIRT7 binding to prevent myocardial injury and apoptosis reduced by I/R [207]. Luo et al. showed that AD-MSCs-EXO with overexpression of miR-126 could effectively reduce cardiomyocyte apoptosis in myocardial border area and prevent myocardial damage [208]. The above studies indicate that MSCs-EXO exhibits a diverse array of delivery pathways, a remarkable homing capacity, and significant anti-apoptotic properties. Furthermore, they provide a valuable research foundation for the potential clinical application use of MSCs-EXO in the treatment of cardiomyocyte apoptosis after MI.

During MI-induced cell apoptosis, not only does oxidative stress play a role, but there is also a loss of ATP and NADH. Treatment with MSCs-EXO increased ATP and NADH levels, reduced oxidative stress, and enhanced activation of the PI3 K/AKT pro-survival signaling pathway. Additionally, MSCs-EXO treatment decreased the phosphorylation of c-JNK, a key activator of pro-apoptotic signaling [209]. This suggests that MSCs-EXO reduces apoptosis at least in part by restoring the bioenergetics of target cardiomyocytes and reducing oxidative stress.

The inflammatory response has been comprehensively detailed in the preceding Sect.” Immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory“and will not be reiterated here.

The new small capillaries are hollow tubular structures surrounded by ECs which are supported by pericytes. The outsourced basal cells and extracellular matrix (ECM) can further enhance the structural stability of small capillaries [210]. In the physiological state, ECs maintain inactive and the surrounding basal cells and pericytes also maintain the normal order of ECs to perform its functions. However, when the environmental and mechanical stresses in the injured tissue change, these stable structures are destroyed [211]. Preexisting ECs in the infarct margin area will produce initial new capillaries by budding [146]. The budding process begins with the breakdown of basement membrane by proteolytic enzymes and the isolation of pericytes. After that, ECs can be activated. With the help of VEGF and other factors, activated ECs escaped from the original capillaries and invaded the temporary scaffold matrix to participate in budding. Their cell characteristics and molecular expression profiles are altered, and they will differentiate into tip and stalk cells with different morphology and functions [212, 213]. The tip cells have a large number of filamentous feet, which are mainly responsible for migration and coordinating the direction of branch formation. During bud elongation, stalk cells proliferate and form new primitive capillary lumen with the proliferation of stem tip cells [213, 214]. The stable budding then begins to transform into mature blood vessels and fuse with existing capillaries. The ECM also gathers around the nascent original capillaries and recruits pericytes to cover the ECs [215]. Ultimately, the blood vessels achieve stability and blood flow normalizes.

Homing ability is the basis for MSCs to participate in angiogenesis [216]. MSCs can migrate and adhere to ischemic tissues through differentiation, direct contact or paracrine, and play a role in promoting angiogenesis [217, 218]. For example, hypoxia and reoxygenation can accelerate the state recovery of MSCs, improve the expression of pro-survival genes and various nutritional factors in MSCs, and indirectly increase the homing ability and angiogenesis of MSCs [219, 220]. In addition, hypoxia pretreating of BM-MSCs can enhance their migration capacity by activating Kv2.1 channels and FAK [221]. The above studies indicate that hypoxia pretreating can improve the survival rate of transplanted MSCs in the infarct junction and promote homing ability and angiogenesis. It provides a good experimental basis and theoretical basis for us to further explore the relationship and mechanism between hypoxia pretreating, homing ability and angiogenesis of MSCs.

In addition to hypoxia, several genes related to angiogenesis can also be directly transferred into MSCs to enhance the angiogenic ability of MSCs. Using MI as an example, MSCs transfected with HGF or VEGF can promote angiogenesis and reduce fibrosis, thereby improving ventricular function in MI-induced porcine models [222]. Compared with MI mice injected with ordinary MSCs, MI mice injected with Ang-1 overexpressing MSCs had a better effect of angiogenic (approximately 11–35% more than the control group) [223]. Other studies have shown that basic fibroblast growth factor can control the migration of MSCs and improve the integration of MSCs with ECs to promote angiogenesis [224, 225]. These studies collectively suggest that appropriate genetic engineering of MSCs is essential to enhance their angiogenic potential.

The regenerative capacity of MSCs is also associated with their differentiation potential. In addition to osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic differentiation potential, MSCs are also capable of differentiating into steroidogenic cell lineages [226], myogenic cells [227], hepatocyte-like cells [228], and cardiomyocytes [229]. However, whether MSCs can differentiate into ECs is still controversial in current studies. At present, only a few studies support that MSCs can differentiate into ECs-like cells [230,231,232]. Most scholars believe that MSCs and MSCs-EXO can promote angiogenesis mainly because they can interact directly with damaged ECs or in paracrine form [233, 234]. After MSCs come into direct contact with the damaged ECs, tunneling nanotube-like structures are formed. This structure allows MSCs to move frequently and almost unidirectionally towards the damaged ECs, thereby resulting in the rescue of aerobic respiration and protection of ECs from apoptosis [235]. In the paracrine studies of MSCs and MSCs-EXO for the promotion of tissue regeneration, MSCs-EXO has been the most extensively investigated in recent years. The current research mainly focuses on the following three aspects: (1) Combining MSCs-EXO with some new molecular materials can improve the therapeutic effect of MSCs-EXO. For example, if MSCs-EXO overexpressing Islet-1 is combined with Ang-1 gel, the retention of MSCs-EXO in the heart can be increased, and its anti-apoptotic effect can be further enhanced to promote angiogenesis, to enhance the anti-apoptotic effect and promoting angiogenesis [236]. After the injection of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles with MSCs-EXO mixed reagents into MI’s heart, the inflammatory period can be transformed into a repair period in advance under magnetic guidance. This results in a reduction of apoptosis, an alleviation of fibrosis, the promotion of angiogenesis, and the recovery of ventricular function [237]. After all, MSCs-EXO mixed new materials are exogenous implants, and whether they have adverse effects on the human body still needs long-term follow-up observation, so we still need to be cautious about their use. (2) MSCs-EXO (or pretreating of MSCs-EXO) were modified by cell engineering will promote angiogenesis and tissue repair. For example, up-regulation of CXCR4 expression in MSCs-EXO can promote angiogenesis through AKT signaling pathway [238]. MSCs pretreated with atorvastatin can improve the survival rate of ECs and increase the expression of VEGF and ICAM-1 gene to improve the therapeutic effect [239]. However, it is unclear whether modification or pretreatment affects the genetic properties of MSCs-EXO, so its clinical application remains to be further investigated. Optimizing the delivery mode of MSCs-EXO can improve the utilization rate and promote angiogenesis. The emergence of new delivery methods, such as intra pericardial delivery [240] and exosome spray [241], has changed the traditional concept that MSCs-EXO can only be used by injection. These advancements may pave the way for new therapeutic strategies and could become a major focus of future research and development in the field of MSCs-EXO.

Therapeutic applications in disease models

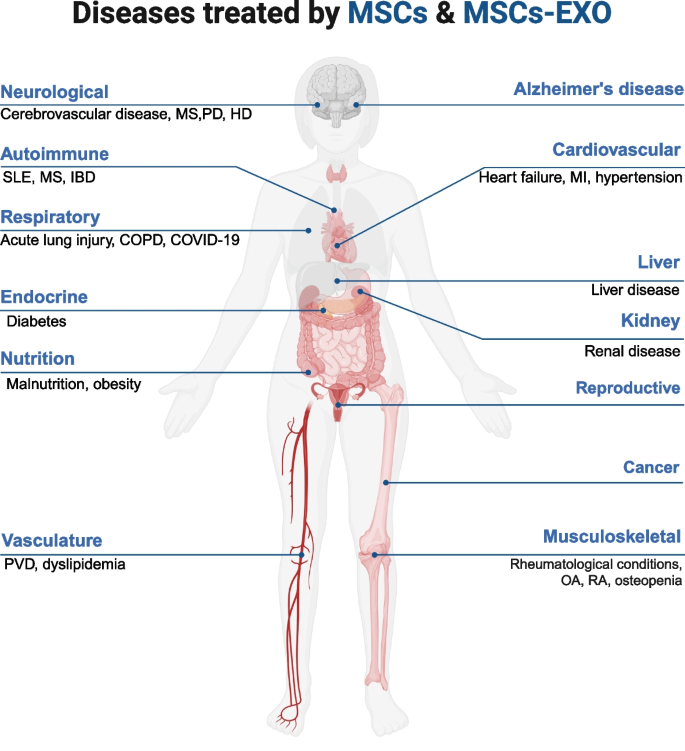

Currently, MSCs and MSCs-EXO have been extensively utilized in clinical studies owing to their promising therapeutic effects. This section will summarize their applications in CVDs, neurological disorders, ADs, MSDs, and other conditions (Fig. 7).

Overview of MSCs and MSCs-EXO applications in Disease Models. MSCs and MSCs-EXO can exert therapeutic effects in a wide range of diseases, including those affecting the nervous system, respiratory system, circulatory system, digestive system, urinary system, reproductive system, musculoskeletal system, immune system, and many others. MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells; MSCs-EXO: MSCs-derived exosomes; MS: multiple sclerosis; PD: parkinson’s disease; HD: huntington’s disease; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PVD: peripheral vasculature disease; MI: myocardial infarction; OA: osteoarthritis; RA: rheumatoid arthritis

Therapeutic applications in CVDs

CVD, a broad term encompassing disorders that affect the heart and blood vessels, is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, posing a major threat to human health and well-being. A retrospective study from 204 countries reported that the number of patients with CVD increased from 271 to 523 million, and the number of deaths with CVD increased from 12.1 million to 18.6 million between 1990 and 2019 [242]. This is a huge challenge for the global health system. MI is an important component of CVD. MI refers to the condition where reduced coronary blood flow, due to various causes, results in ischemia and hypoxia of cardiomyocytes, leading to necrosis in the myocardial region supplied by the affected coronary artery [243]. MI can be classified into AMI and chronic MI (CMI) based on the course and nature of the disease. The primary cause of AMI is acute thrombosis. When a coronary artery is abruptly occluded by an acutely dislodged thrombus, myocardial necrosis can occur within minutes to hours. However, CMI is a long-term pathophysiological process characterized by the gradual expansion of coronary atherosclerotic plaques, leading to progressive luminal narrowing and resultant myocardial ischemic injury. The exact timeframe for CMI development remains variable [244]. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis and subsequent inflammatory response will lead to local tissue fibrosis, scar tissue formation and poor ventricular remodeling. They can have adverse effects on the regeneration of the heart, and some patients may progress to HF or even death [245]. All the above pathophysiological processes occur throughout the progression of the disease, both in the AMI and CMI. Therefore, it is of great significance to explore a new biologic therapy to alter or reverse these pathophysiological processes.

In recent years, MSCs and MSCs-EXO have emerged as promising therapeutic modalities in the clinical treatment of CVDs, including MI. We have summarized the clinical application of MSCs in Table 1 and found that BM-MSCs are the most commonly utilized type for the treatment of MI, followed by AD-MSCs and UC-MSCs. In contrast, DP-MSCs are primarily used in basic research, with clinical studies predominantly focusing on pulp and bone regeneration following tooth injury. Although a large number of preclinical studies have shown that MSCs have a positive effect on the treatment of MI, the results of existing clinical trials have been polarized. For example, after autologous BM-MSCs transplantation in 10 AMI patients who received standard therapy, Bodo et al. found that, compared with MI patients receiving standard therapy, those in the cell therapy group exhibited a significant reduction in the percentage of infarct size relative to the total left ventricular area and a significant increase in the velocity of ventricular wall motion in the border zone [246]. This suggests that BM-MSCs may possess reparative effects on cardiomyocytes following MI. According to another study involving 69 patients with AMI who were randomized to receive either BM-MSCs or saline following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within 12 h of symptom onset, left ventricular function was significantly improved in the BM-MSCs treatment group (n = 34) [247]. With the deepening of research, more and more clinical studies have confirmed the safety of MSCs in clinical application and its protective effect on myocardial tissues after MI [248, 249]. However, some studies have shown that MSCs have a limited therapeutic effect on MI. For example, Wollert et al. [250] showed that patients treated with MSCs did not show a significant increase in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) compared to controls. In addition, according to another study in Norway, Patients in the acute stage of MI did not significantly improve left ventricular function after intra coronary injection of BM-MSCs [251]. Other studies have demonstrated that, while patients treated with MSC injections exhibited improved LVEF, reduced left ventricular end-systolic volume, enhanced stroke output, and smaller MI scar areas, there were no significant differences in overall mortality or cardiovascular mortality compared to those receiving conventional therapy [252]. Although the above data indicate that MSCs are not ideal for the clinical treatment of MI, most studies show that the effect of MSCs on the clinical treatment of MI cannot be ignored, compared with untreated group, LVEF and ventricular function were improved significantly. We analyzed the reasons for the large heterogeneity in the above studies as follows: (1) The total number of participants in the study was too small for statistical analysis; (2) Different amounts of imported MSCs or different injection sites lead to heterogeneity of treatment outcomes [253]; (3) Different preparation techniques and algebras of MSCs lead to different therapeutic effects; (4) There are differences in the treatment time window.

It is noteworthy that our review of clinical studies revealed that the majority of trials utilized coronary artery administration, whereas IT and transendocardial stem cell injection (TESI) were employed in only a minority of cases. In recent years, stem cell pericardial implantation technology has emerged as a novel approach and has gradually garnered attention. Although coronary artery administration remains the predominant method for stem cell therapy in MI, significant variability in clinical outcomes persists. A study by HOPP et al. demonstrated that, compared with the control group receiving sham injections, the experimental group of 15 patients who received intra-coronary injections of BM-MSCs did not exhibit significant improvements in cardiac function, and the reduction in infarct size was not statistically significant [274]. Although a few studies have indicated that MSCs treatment may be ineffective, it is important to note that no serious adverse reactions have been observed following autologous transplantation of MSCs. This suggests that, despite the controversy surrounding its efficacy, the safety of MSCs in clinical applications is well-established. In addition to autologous transplantation, MSCs are also suitable for allotransplantation. While allogeneic MSCs exhibit low immunogenicity, immune rejection may still occur in some cases. For instance, it has been demonstrated that recipients of completely mismatched allogeneic MSCs may develop memory T cells that can trigger immune rejection [285]. The survival time of allogeneic MSCs post-transplantation is typically shorter than that of autologous MSCs, which may influence therapeutic outcomes. Additionally, MSCs derived from different tissue sources exhibit variations in biological properties, culture characteristics, and differentiation potential, potentially leading to differences in therapeutic efficacy.

Although MSCs-EXO has shown certain potential in clinical studies of atomized inhalation in the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia and other diseases [286], its application in clinical studies is still insufficient compared with MSCs. The administration route and dosage optimization of MSCs-EXO need to be further explored. In addition, MSCs-EXO is rapidly cleared in the body, has poor stability, and is susceptible to temperature, pH and mechanical stimulation [287]. Therefore, it is crucial to develop effective delivery systems to enhance their persistence in vivo and to establish appropriate preservation methods to ensure their efficacy and stability. Future research should further investigate the clinical applications of MSCs and MSCs-EXO to fully realize their therapeutic potential.

Therapeutic applications in neurological disorders

Neurological disorders rank fourth in the global disease burden [288]. Its common clinical manifestations include sensory and motor dysfunction, as well as impaired cognitive function. Given the limited regenerative capacity of nerve cells following damage, these conditions often result in long-term or even lifelong challenges for patients [289]. In therapeutic interventions, the timely and effective repair of injured neurons is crucial for maintaining normal neural function. MSCs represent an ideal cell source for neural regeneration and repair. By secreting a diverse array of bioactive factors, including miRNAs, proteins, and growth factors, MSCs not only promote neuronal survival and nerve regeneration but also inhibit inflammatory responses, thereby significantly enhancing neural function [290].

In recent years, MSCs and MSCs-EXO have been widely used as an alternative therapy for the clinical treatment of neurological diseases. We summarized the recent clinical applications of MSCs and MSCs-EXO in neurological diseases in Table 2. Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a neurodegenerative disorder resulting from mutations in the SMN1 gene [291]. In patients with SMA, the capacity of MSCs to cross the blood–brain barrier can be leveraged to maximize the therapeutic efficacy of IT [292]. Meanwhile, intravenous injection (IV) is more appropriate for targeting organs such as the lungs, spleen, liver, bone marrow, and thymus, which are characterized by their propensity for cellular diffusion [293]. Studies have demonstrated that IV of MSCs promotes the release of neurotrophic factors and cytokines, facilitating their entry into pathological tissues. This approach has been shown to significantly improve the tibial nerve motor amplitude response in patients with SMA, thereby demonstrating the tolerability and safety of MSCs in SMA treatment [294].

MSCs treated by IV injection in combination with IT is considered a promising therapeutic strategy for treating neurological disorders. Lu Z et al. [327] investigated the use of long-established IV administration in combination with IT infusion of UC-MSCs for treating relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) and neuromyelitis optica (NMO). During a 10-year follow-up of patients with NMO spectrum disorder (NMOSD), no adverse reactions indicative of intolerance, such as tumor formation or peripheral organ/tissue disease, were observed in either RRMS or NMOSD patients. This suggests that the combination of IV and IT administration is safe and feasible. Additionally, the study by Jamali F et al. [317] found that in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) treated with UC-MSCs, those receiving two doses of IV and IT administration exhibited significantly greater improvement in clinical symptoms compared to the control group, which received a single dose of IV and IT treatment. The downregulation of inflammation-related genes, including TNF-α, TAP-1, and miR-142, indicates that the combination of IV and IT administration is effective. However, while the current study supports the effectiveness of combining IV and IT administration of MSCs for neurological disorders, further clinical trials are necessary to verify its long-term effects and determine the optimal dosing regimen.

Therapeutic applications in ADs

ADs constitute a complex class of disorders whose etiology remains incompletely understood. Although there may be some similarities in the clinical presentation of different ADs, each condition exhibits its own distinct characteristics [328]. ADs are typically characterized by the activation of autoreactive T and B cell clones [329]. In these conditions, the immune system erroneously targets the body’s own normal cells, resulting in a diverse array of symptoms and pathological changes.

SLE is one of the most prevalent ADs. Recent studies have demonstrated that MSCs and MSCs-EXO exhibit potent immunomodulatory effects in the treatment of SLE, influencing immune-related cells such as T cells, B cells, NK cells, and macrophages. The immunomodulatory properties and multidirectional differentiation potential of MSCs and MSCs-EXO make them valuable tools for treating ADs. However, due to concerns regarding the carcinogenic risks associated with genetic mutations, genetic instability, and excessive proliferation and differentiation of MSCs, MSCs-EXO is considered a more favorable option for future SLE treatments [330]. Studies have demonstrated that in a non-obese diabetic (NOD) rat model, treatment with AD-MSCs-EXO and BM-MSCs-EXO can effectively repair damaged neurons and astrocytes, specifically inhibit the overactivation of T and B lymphocytes, and mitigate autoimmune damage to islet cells. This results in improved cognitive function and reduced blood glucose levels [331]. We summarized the clinical application of MSCs and MSCs-EXO in ADs in the past 5 years (Table 3). In the trial conducted by Kamen DL et al. [350], six women with refractory SLE were treated with MSCs at a dose of 1 × 106 cells/kg. The results indicated a downward trend in autoantibody levels, while the GARP-TGF-β index in B-cell serum increased. These findings suggest that MSCs exert a systemic immunomodulatory effect consistent with the observed clinical treatment outcomes. In a triple-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial conducted by Fernandez et al. [351], patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS) were followed for 12 months after infusion of autologous AD-MSCs. Only one serious adverse event (a urinary tract infection, deemed unrelated to the study treatment) was observed. These findings suggest that the use of AD-MSCs in treating SPMS is both safe and feasible. However, data from this trial did not yield significant results for potential markers of therapeutic effect in immune testing. Therefore, larger studies are necessary to further investigate the therapeutic benefits of MSCs. In the trial conducted by Chun S et al. [352], seven patients with lupus nephritis (LN) received an intravenous infusion of 3.0 × 106 cells/kg BM-MSCs, with no dose-limiting toxicity observed. Additionally, in animal models, BM-MSCs distribution in the kidneys persisted until day 7. These findings demonstrated the safety and tolerability of BM-MSCs in LN patients and identified 3.0 × 106 cells/kg as the maximum tolerated dose for this patient population. Given the relatively limited number of patients with ADs currently treated with MSCs and MSCs-EXO, the existing results may be subject to bias. Therefore, it is essential to conduct further experimental validation in larger patient populations.

Therapeutic applications in MSDs

MSDs is a common group of diseases affecting human health, usually involving muscles, bones, tendons, ligaments, cartilage and related tissues. The main clinical symptoms include pain, stiffness, swelling and limited motor function [353]. This condition is often attributed to a variety of factors, including repetitive strain, poor posture, chronic stress, or traumatic injury [354]. OA and RA are among the most prevalent MSDs. OA can lead to intractable pain, limit daily activities, and significantly reduce patients’quality of life, although it is not inherently a fatal condition. RA, on the other hand, is a systemic autoimmune disease that can affect multiple joints throughout the body and is not secondary to OA. Currently, clinical treatment primarily focuses on pain relief, rehabilitation, or surgical intervention; however, these approaches are not effective in preventing the progression from OA to RA [355]. As a cell-based therapy, MSCs and MSCs-EXO demonstrate significant potential in the treatment of MSDs. MSCs have the capacity to differentiate into osteoblasts and chondrocytes, and they promote cartilage repair and regeneration through the secretion of various bioactive factors, including growth factors and cytokines [356]. MSCs-EXO can promote chondrocyte proliferation, inhibit cell apoptosis, and enhance the synthesis of cartilage matrix [357]. These characteristics underscore the significant potential of MSCs and MSCs-EXO in the cellular therapy of bone and cartilage diseases.